Tree's Company

Surviving 10Weeks With a Thornless Honey Locust: My Story

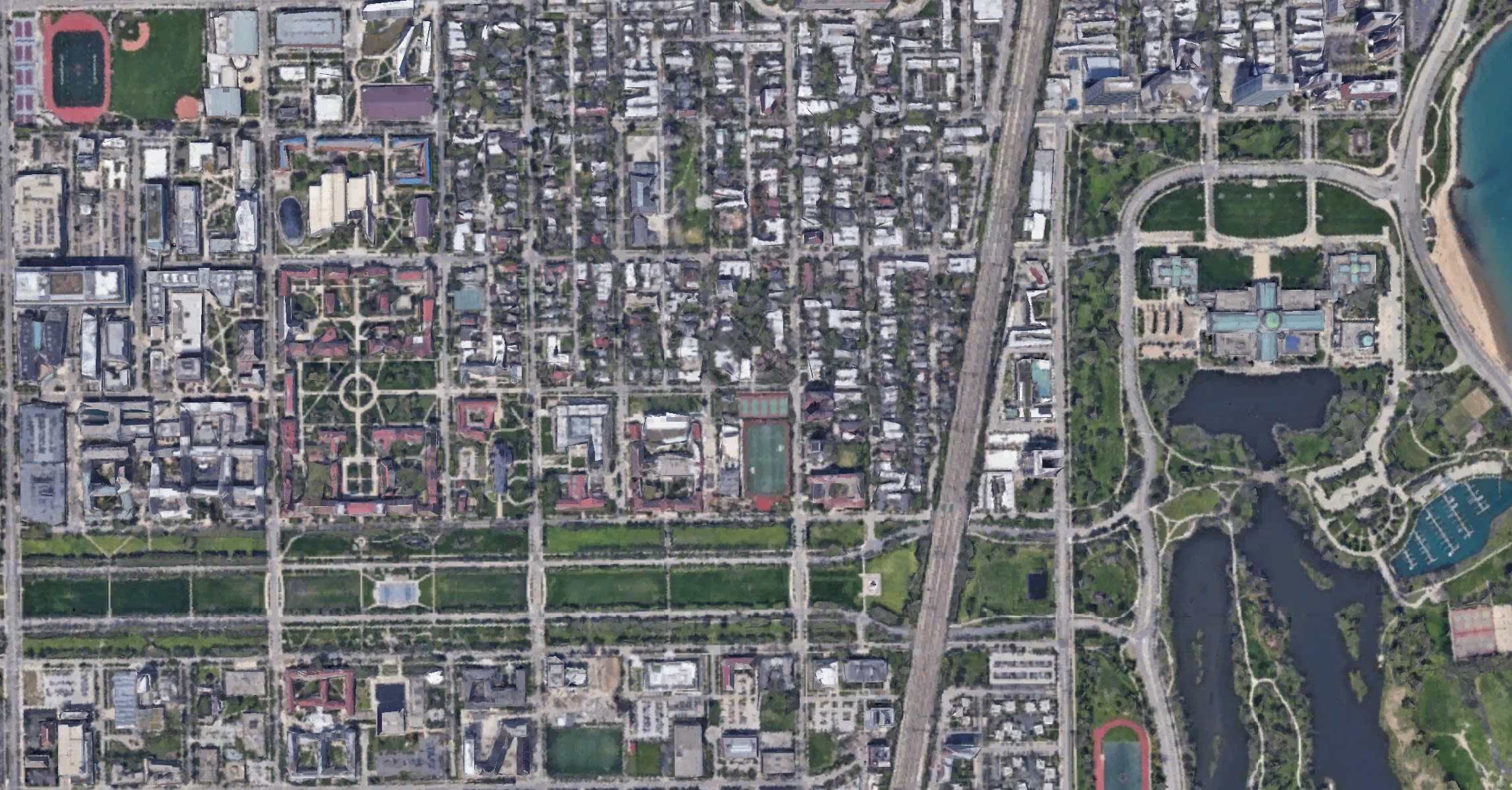

Very early on in this class, we read about ‘amateur eyes’, which might prevent us from seeing many aspects of our everyday environment. I have made an effort to suppress these eyes in our observations and writings about the Great Nearby, but there is only so much you can do when you remain, on a purely informational basis, an amateur. As such, it is important that we take a deeper look at this Great Nearby. The pristine environment that was once found here, the history of development by humans, and the modern impacts on and of this area are valuable in their own right, and can grant us answers to some of our questions (and grant us better questions, as well). To begin with, a quick and relatively arbitrary delineation of what I will call my Great Nearby. Hyde Park is the vast majority of my Great Nearby, but I will extend the Southern border of my area to 61st Street, because it would be weird if my living space and the location of our class wasn’t included. This extension also includes the Midway, where my tree is located, which has a fascinating natural history that gives some nice insight into some of the things that can impact human development. I will also include Jackson Park, because I visit it from time to time, but not Washington Park, because I don’t. This Great Nearby, as I can see it, has trees lining most streets and lots of lawns. It has the University of Chicago, whose campus contains a variety of unique natural pockets. It has a couple highly developed parks which nestle Hyde Park in an embrace of green on maps, and there is even a lakefront. What used to be here?

Hyde Park, like most of Chicago, was originally made up completely of inhospitable marshland. The vast majority of the ground was soft and wet, and the small patches of dryness were tough, sandy, and infertile. This infertile soil and proximity to Lake Michigan is foundational (although it makes a terrible foundation, ba dum tiss) to the history of development of Hyde Park. Hyde Park is the unassuming little suburb it is today in large part because the agricultural hopelessness of its land prevented any meaningful farm industry from developing this land, allowing it to remain largely undeveloped before Chicago’s growth ballooned to a point where a little wet dirt was not going to stop anyone from developing. Eventually, the area reached a point where it was potentially quite desirable. A man named Paul Cornell intended to make the area into a wealthy resort style suburb with more expensive real estate - he even named the area Hyde Park to evoke thoughts of the iconic London neighborhood. Despite the grossness of a sequestered paradise for the wealthy elites, it is largely because of this dream that Hyde Park has as much of a history with nature as it does. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead (kind of a big deal, you ever heard of Central Park?) was hired to beautify Hyde Park, and it was him that designed the trifecta of Jackson Park, the Midway, and Washington Park. Olmstead saw how uninspiring the natural soil and flora was aesthetically, so he instead endeavored to connect the neighborhood as a whole to its one redeeming feature: Lake Michigan. The Midway was originally supposed to feature an extensive waterfront of canals and water features that would decorate the length of Hyde Park with an imitation of the lakefront. However, the development was never completed, in large part due to the financial impact of the Great Chicago Fire. When we think of human development in urban spaces, there is usually a lot of intention behind things, although rarely is that intention good. However, in this case, the Midway is an accident left behind by a failed development project. It is almost akin to a human development version of the vacant lots we discussed, where out of an unused space, new and novel things might sprout out of it. Sure, in vacant lots that’s wild clover and on the Midway it’s an ice skating rink, but the parallel is interesting nonetheless. So Olmstead, though he completed development of Jackson and Washington Park, failed to realize his dream of bringing the waterfront across Hyde Park. However, if you ever try to use the soccer field after a rainy November morning, you’ll see a glimpse of Olmstead’s vision.

The planting of trees in the Hyde Park area was well underway as part of Cornell’s vision, but the University of Chicago kicked it into overdrive. The University’s tree survey map shows the massive impact of the University on the treelife in the area. However, the planting of trees was complicated by the unfertile soil of the marshland. The solution was to ship in massive quantities of fertile, dark prairie soil that would allow the trees to grow. As I’ve seen in my observations, there is no soil in the area that seems like it would be there naturally; humans have had to build ecosystems in Hyde Park literally from the ground up.

So what of this Great Nearby today? The gardens of UChicago and the parks of Hyde Park, as well as the trees along the street and in people’s front yards, all are, at this point, a well established ecosystem of its own. The natural areas could not really be described as pristine or novel, nor are they, outside of a few university gardens, of much utility agriculturally. The nature primarily exists for the enjoyment of humans - it shades the streets in summer and provides spaces for activities like the rink on the Midway or the races in Jackson Park. It also looks pretty good on UChicago brochures. The ecosystems are tightly managed and isolated, which limits the possibility of natural processes to occur as they would in nature, necessitating human management like a regular flow of new soil into gardens and to help new trees grow. Even the Midway is cut up by roads, despite it seeming like an unbroken stretch of greenery. Grass is mowed regularly, which can’t be good for the grass. Certain animals are deemed acceptable for human coexistence, whereas other, sharper toothed ones no longer occupy the same spaces, which potentially disrupts the equilibrium of the food chain and definitely leads to some very fat squirrels. There is plant and animal life both native and from the other side of the world present. In terms of disservices, the transition away from elm trees into more oak trees has surely increased the danger of getting hit in the head with an acorn, but perhaps not enough to warrant action. Despite all that we’ve learned in this class about the many ways that urban ecology can be a problem for both the urban and the ecology sides of it, reflecting on that has only made me more sure of its importance. Hyde Park without parks or trees would be completely miserable to live in and walk through, and so much of the information I take in when living my life, both before and even more so now, is about the nature I see and hear. Plus, without nature in Hyde Park, I probably wouldn’t get to take this class, so how’s that for an ecosystem service?

Owls have very well trained eyes

Owls have very well trained eyes

My tree is a honey locust. Honey locusts are large deciduous trees that are found all across the United States. They are notably hardy, making them well suited to the harsh soil and weather conditions that can afflict the Chicago area. This allows them to thrive in a variety of places, making them often an invasive species. They are, however, native to Northern Illinois.

However, while my tree is in its natural habitat, that is just about the only thing about it that is consistent with the classic honey locust

One of the most iconic aspects of the honey locust is the sharp clusters of thorns that cover its trunk and branches. These thorns are a defining feature. My honey locust has none.

The thornless honey locust, Gleditsia triacanthos var. Inermis has been cultivated without thorns. This makes it a much safer choice to line a city's streets with, at the cost of leaving its rough bark and massive seed pods vulnerable to the creatures that would eat them.

Except that my tree doesn't have seed pods, either. Nor does it have creatures to eat them.

The honey locust seed pod holds a massive legume with nutritious and sweet meat inside (the taste is where the honey in the name comes from). These seeds can be a mess to sweep up from city sidewalks, so more commonly the thornless honey locust is also infertile and fruitless.

The creatures that once wished to eat these seeds are long extinct. Ancient megafauna - mastodons and giant ground sloths - once fed from trees like the honey locust. In an effort to prevent its seeds from being digested by massive herbivores, the honey locust developed its thorns in an effort to dissuade them. Humans are partially responsible for the extinction of the megafauna, and also responsible for the disappearance of the thorns.

Although my tree, a honey locust on the corner of 59th and University, does not have thorns or seed pods, it does have tiny leaves that will turn bright yellow over the course of autumn. It sits in a row of similar trees, almost all honey locusts as well, no thorns or seed pods to be found.

This tree will be the focal point of my Great Nearby as a whole, and will be the aspect of it that I observe most closely in an effort to understand it and the ecosystems around it.

My Great Nearby and the Four Natures

One way to categorize the way urban areas interact with nature is to use Ingo Kowarik's model of the four natures. In Kowarik's eyes, nature in developed areas could be essentially divided into four different categories:

1. Natural habitats that are either pristine or developed so as to remain pristine, similar to how they may have operated before human interaction.

2. Nature that has been developed for human use, such as agricultural land.

3. Highly developed urban green spaces like parks and personal lawns.

4. Novel nature cropping up in vacant lots, creating new urban ecosystems.

The four natures concept is a good way to categorize the different ways that nature can exist in an urban environment. Hyde Park is surrounded on three sides by prime examples of Nature 3 - Jackson Park, the Midway, and Washington Park all have examples of the classic, highly developed urban green space. Nature 1 is also relatively accessible, with small nature preserves in Washington Park and on South Shore. These are both quite small, though, so for a larger pristine green space, you might have to go all the way towards Waterfall Glen on the very edge of Chicago. Nature 2 is even worse. This one is the one that I have the hardest time grasping the definition of, but if you’re looking for agricultural land, there really isn’t any until you’re at the very Southern edge of Cook County. Nature 4 is usually unlabeled, and so is hard to find on a map. There are undoubtedly pockets of naturally occurring wildlife throughout Hyde Park, but to find a real significant plot of land that embodies the idea, the South Steel Works are the most convenient option. There is also Lake Michigan, which I think can fit into all four categories depending on where you look: there are relatively untouched parts of the ecosystem, as well as heavily managed areas for commercial and recreational purposes.

Hyde Park is very green, but that greenery almost entirely consists of the highly managed green spaces of Nature 3. There are small pockets of unmanaged wildlife in some spaces, some pristine and some novel, but they are small and hard to find. Agricultural and commercial green use is, as far as I can tell, completely absent within the actual city of Chicago as a whole, although this dearth is more than made up for as soon as you look beyond the city’s edge.

The third kind of nature is the easiest for humans to interact with on a day to day basis (assuming you’re not a farmer or wildlife ranger). It is made to be walkable, maintained to be safe, easily accessible within a city, and usually looks intentionally aesthetically pleasing. Leaving these areas unmanaged for a while could certainly lead to some new and exciting ecosystems, but it also might drive away human visitors, potentially alienating city inhabitants further from the natural world. I grew up in the woods, so I am not an expert on how city people engage with nature on the whole, but there is definitely a fine line between letting nature run wild and letting the city fall apart. Highly managed green spaces has long been the compromise between the two, but if the community were engaged with its local green spaces in a more direct way, there may be a way to allow natural processes to occur without compromising an enriching relationship between human and wilderness.

My Great Nearby and Interspecies Relationships

Until this past week, I had very little luck seeing animals interacting with my tree. I saw a single tiny spider once, and didn’t have time to get a good look at it before it disappeared into the underbrush. However, I recently got very lucky and, in a span of about five minutes, saw both a squirrel and a downy woodpecker (I believe, my bird identification skills are questionable) interacting with my tree. The woodpecker didn’t linger, sitting on some of the outer branches to pose for a minute or so before flying off into an area with a denser tree cover. The squirrel, however, did something very interesting. One of the defining features of my tree is the strange, twisted branch that stretches all the way across 59th street. I thought it might break under its weight or even be cut off by humans in fear of it falling and potentially damaging parked cars. I also had previously explained the lack of fauna, in particular squirrels, on my tree as being due to my tree’s infertility and lack of edible bits. And indeed, the squirrel on my tree did not use it to forage. It used that long, horizontal branch to safely cross the street. That simple interaction massively expanded my perception of how diverse natural systems can interact and adapt for an urban space. It wasn’t anything mindblowing, but I simply hadn’t thought to consider those types of interactions. That my honey locust, which lacks seed pods and flowers to attract fauna, could still be utilized by animals as a safety measure in an urban space, was definitely interesting.

Aside from my tree providing safety from the road, there were other human-nature interactions at play. One major one is the removal of fallen leaves from the area around my and other trees. My tree has sidewalk and road underneath its canopy, and those areas seem to be routinely cleared, as I saw very little leafage on the ground, even though I observed considerable loss of foliage in the branches. This combination of man made surfaces under the tree and routine clearing of decaying leaves certainly affects the natural processes of the tree and its ecosystem. Normally, the fallen leaves of trees decompose, attracting insects both to feed on and to shelter from winter, and eventually return nutrients to the soil, promoting plant growth and probably feeding the tree back a fair bit. However, when the leaves fall onto concrete or are cleared away, this cycle is nipped in the bud, making it probable that humans have to then also fertilize and caretake the plant life present to make up for it. It is interesting that even those processes that might be relatively unaffected by an urban environment otherwise are still tightly managed. It seems like more work for everyone.

The biodiversity of the Great Nearby is tightly managed. Just about every major plant in the area around my tree seems to be clearly planted and pruned by humans. For many of the plants, the reason for their existence is clear: my honey locust is convenient because it lacks thorns and massive seed pods that clutter the paths and roads below. Next to my tree is the North Winter Garden on the midway, which seems to be planted to specifically flourish during these colder months. It has quite a few evergreen trees, as well as bushes with bright red berries and tall grassy clumpy plant things. I haven’t observed much in the way of humans managing fauna, outside of some weird professor ritualistically murdering gypsy moths, but there are definitely animals that would elicit human intervention. Invasive species like the gypsy moths definitely have some people on the lookout, and larger animals, especially predators, would definitely not be allowed to flourish in the middle of Hyde Park.

My Great Nearby and Ground Cover

The Great Nearby of UChicago has a lot of impermeable surfaces. One need only try to walk past Cobb after a rainy day to fully appreciate that fact. Although drainage infrastructure generally prevents the water from lingering on roads or walkways, that still prevents the precipitation from naturally sinking into the ground as it would in more soil covered areas. There are areas with more permeable surfaces of course, and these can vary a surprising amount in properties and human impact. Most of the trees, bushes, and flowers planted in and around the area have a dark, packed soil with some small stones and wood chips mixed in. While the wood chips make it very clear that this is a human created environment, most of these areas are relatively undisturbed, with plantlife naturally decaying into them. The soil is very close packed, but the larger, mulchier parts mixed in probably improve the permeability of the land a fair bit, and the abundance of plant life also helps that. I didn’t see any plots of empty dirt with no plant life, which would be almost as bad as cement in terms of permeability. I also am not sure that the simple existence of plant life is a perfect indicator of whether a surface is permeable. For example, the bushes planted along South Ellis when crossing the midway are seemingly contained to a concrete box - maybe the dirt goes through underneath, but I feel like it’s doubtful. Even if soil can absorb more water, if the water can’t travel through the soil to runoff, the benefits are pretty limited to that specific area, fragmenting the various habitats’ natural cycles. On the other side of that is a segment of paved sidewalk that clearly has a tree root pushing up on it from underneath. If a tree can travel underneath the sidewalk, water probably can as well. This ties into Beatley and Manning’s The Ecology of Place. In it, they argue for a greater connectedness of natural processes across urban ecosystems. The water cycle is something that naturally occurs over a great deal of space, so restricting the flow of water to tiny spots of greenery throughout the city and ushering the rest out via storm drains is by no means natural. The movement of water through a system can lead to more even, nutrient rich soil. The lawns in my Great Nearby all contain topsoil that is clearly placed by humans on a semi regular basis. A truly sustainable ecosystem should be able to maintain an enriched topsoil through natural decay and water.

One interesting detail I noticed was that the sidewalk next to my focal tree is not a sidewalk at all, but a gravel path over dirt. This is very unusual for such an urban area, and I’m not sure why. The fact that I never took notice of it seems to me to show that it isn’t particularly inconvenient, and it is surely more permeable than the concrete sidewalk across the street. This sort of natural integration with human activities is very reminiscent of Leopold’s Land Ethic. The idea of living with natural life as common citizens of the same land is one that cities struggle with massively. Even among greenification movements, the rhetoric surrounding them is very often one that emphasizes the positive impact nature has on humans. The Land Ethic changes, not necessarily the movements themselves, but simply the mindset that guides them. It is basically just the Golden Rule expanded to include all living things. If it were applied, people would be much more inclined to coexist with nature, not because it is convenient or enlightening, but simply because not to do so would be cruel and oppressive. A freely operating water cycle would become a moral obligation rather than simply a nice thing to do to make the city prettier.

My Great Nearby and Ecosystem Services

My focal tree, and the nature around it in the Great Nearby, provide quite a few services to the city in minor and major ways. It helps with carbon capture, reducing emissions and converting greenhouse gases into oxygen. It and the soil it’s planted in help with water retention, decreasing the severity of any flooding.

In addition, during the warmer months, the canopy of the trees provides shade and cover, giving people cover from the sun and decreasing the urban heat island effect. Decreasing the heat island not only decreases health risks like heat stroke, but it also reduces the use of air conditioning, which is both environmentally and economically beneficial.

The leaves dropped by my tree provide cover and nutrients for decomposers and other small insects, helping to maintain some ecosystem cycles that allow the nature in the Great Nearby to be more self-sustaining, which makes maintenance less necessary.

There are a few changes that could be made in order to improve and expand the ecosystem services here. Developing green roofs would cool cities, improve air quality, and could even be used as functional gardens to provide food. Reducing lawn grass in favor of more native ground cover would require less maintenance from humans and would most likely interact more copacetically with the other flora and fauna, giving rise to a natural flourishing of the ecosystem.

My tree at the start of my observations had all of its leaves, with only a few here and there showing tints of yellow.

During this period, there were often small insects flying near the ground during the day, and the weather was quite warm

As the weeks passed, the leaves steadily turned yellow, but the canopy largely remained intact.

As it got a bit colder, I saw very few insects, excepting those which had small nests or shelter in the bark or near the roots

The storm seemingly accelerated the natural process of leaf fall, as the strong winds blew huge amounts of the already yellow leaves off the branches.

The day after the rainfall, the lichen and moss that cover the trunk of my tree were especially vibrant.

I had hoped to see some worms or insect activity in the ground after the rain as well, but the dirt surrounding my tree stayed static. I'm not sure why the soil surrounding my tree seemed so uninhabited by animal life.

By late November, just about every leaf on my tree had fallen, leaving the branches skeletal. Quite a few of my tree's branches also fell in the process, perhaps as a delayed impact of the storms

From November onward, I never saw a single animal interacting with my tree. It got cold, I guess.

This class has been a lot of fun to take. I didn’t expect to get as much insight as I did from such a drawn out project. I thought that I would basically go through the motions, have some fun with it, but mostly just get it done in conjunction with the rest of the work. However, the level to which my personal experiences with Hyde Park and my tree informed and expanded the way I looked at the course material in this class and in the other classes I took was legitimately shocking. The more I watched my tree and its surroundings, the more I understood the discussions we had and the writers we read.

The effect went both ways; at the beginning, my observations on my tree were limited not by lack of care, but simply because I didn’t know what to look at or why. Only a few weeks later, I was noticing things about the animals’ behavior around my tree, and the things on the ground surrounding my tree, and making logical connections and conclusions based on those observations. That level of critical thinking beyond the simple data points was a really cool thing to discover and hone across the last few months. It was frustrating that the activity of my tree seemed to ebb just as my observational abilities came into their own - by the time I really felt capable as an observer, my tree’s leaves had all fallen and there were less and less animals in the area. I also wish I had gone to see my tree more often to collect data. Having only 10 recorded data points for all those months just doesn’t feel like a sufficiently deep look at what the tree went through.

Having an obligation to spend time outside was a welcome requirement for this class. The pandemic and my leave of absence has left me more or less an isolated hermit on campus, so I was glad that this tree could get me out of the dorms and into the field. There were a few people who I had lost contact with that I only saw again because I ran into them while outside doing work for this class. Otherwise, I probably would have just resigned that friendship to being lost to the coronavirus.

The shorthand story somehow both exceeded and did not reach my expectations. I surprised myself with how creative I wanted to be with it, but constantly found myself limited by a lack of proficiency with the software. Maybe it would be better with another project’s worth of practice, or maybe I’m just not a fan of shorthand, but I’m still not happy with quite a bit of the formatting. Nevertheless, I was surprised by how cleanly the narrative structure of the whole thing fell into place, and how the pictures and diagrams I happened to have accumulated over the course of the quarter managed to work well with my thoughts and reflections. In the end, this quarter has been incredibly taxing, but much more rewarding in the moment and going forward as an observer.

Bibliography

Chicago Historical Society Archives, Jean Block, South Parks Commission Historical Register, University of Chicago Archives and Lee Hall’s Olmsted’s America

May Theilgaard Watts, The University of Chicago Archives’ Trustees Minutes, The University of Chicago Archives, Jean Block’s The Uses of Gothic

The University of Chicago Archives, Jean Block's The Uses of Gothic and Jane Brown's The Gardening Life of Beatrix Jones Farrand

Hill, John. “Guide to Chicago's Twenty-First-Century Architecture.” JSTOR, University of Illinois Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctv1q16r8d.22

“Honey Locust: Bates Canopy: Bates College.” Bates Wordmark, 9 Dec. 2021, https://www.bates.edu/canopy/species/honey-locust/.

Authors Joe Boggs, and Joe Boggs. “Honeylocusts and Mastodons.” BYGL, https://bygl.osu.edu/node/959.

“Thornless Honeylocustgleditsia Triacanthos Form Inermis.” Thornless Honeylocust Tree on the Tree Guide at Arborday.org, https://www.arborday.org/trees/treeguide/TreeDetail.cfm?ItemID=852.