Tree & Me

A tour through the Hyde Park area and among her trees.

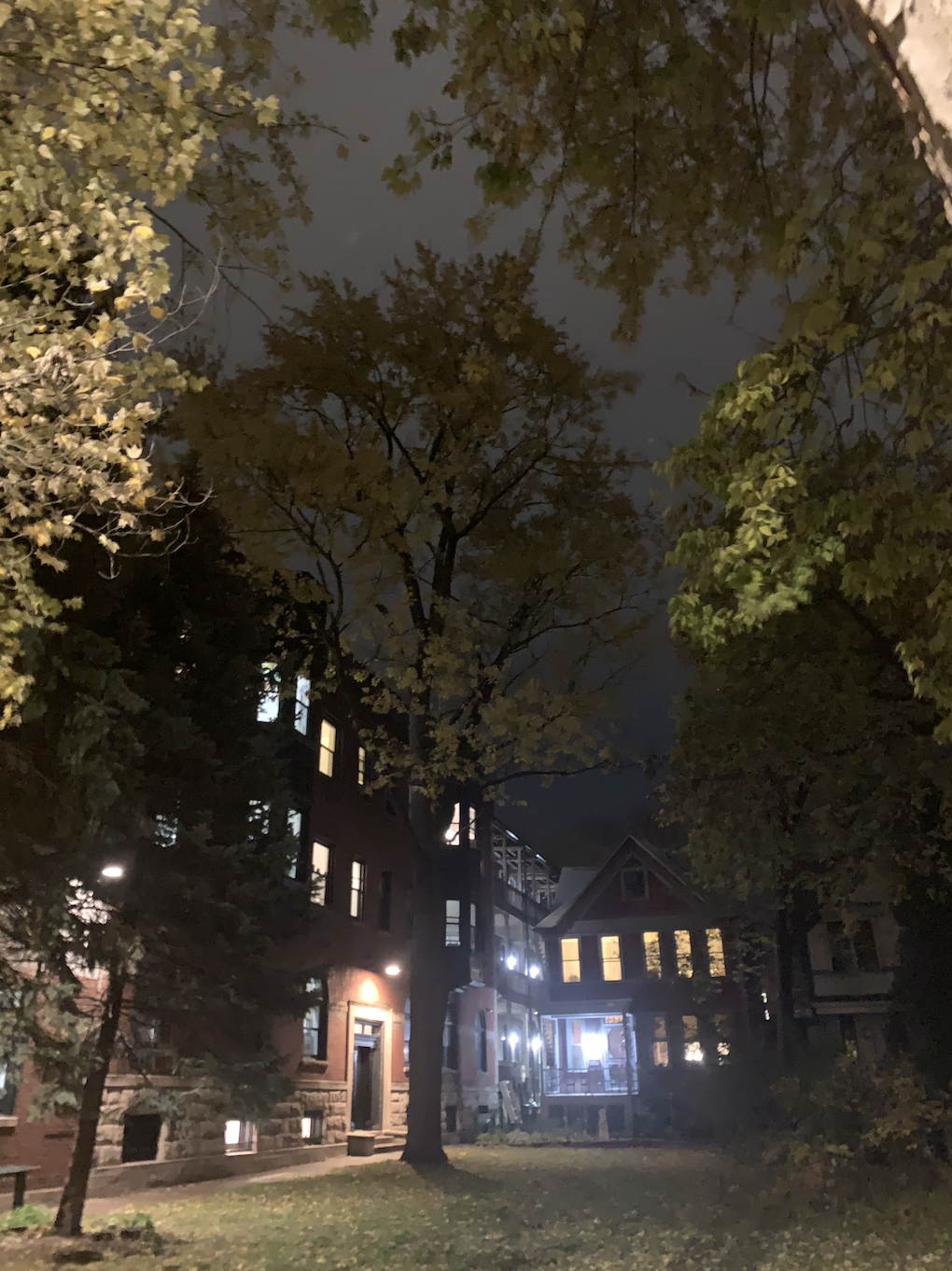

Near corner of 57th and Cornell in Hyde Park, Chicago. Right by the Pepperland, otherwise known as my focal tree.

Near corner of 57th and Cornell in Hyde Park, Chicago. Right by the Pepperland, otherwise known as my focal tree.

Walking down tree-lined 57th Street, just after passing Harper Foods, you will come across the Pepperland. Reminiscent of some Wes Anderson film, the structure holds an interesting place in the history of Hyde Park. Just behind the Pepperland, you will see her. A beautiful silver maple, situated on an empty lot accompanied by other greenery including some coniferous trees, other deciduous trees, and a bush with some flowers, among other things.

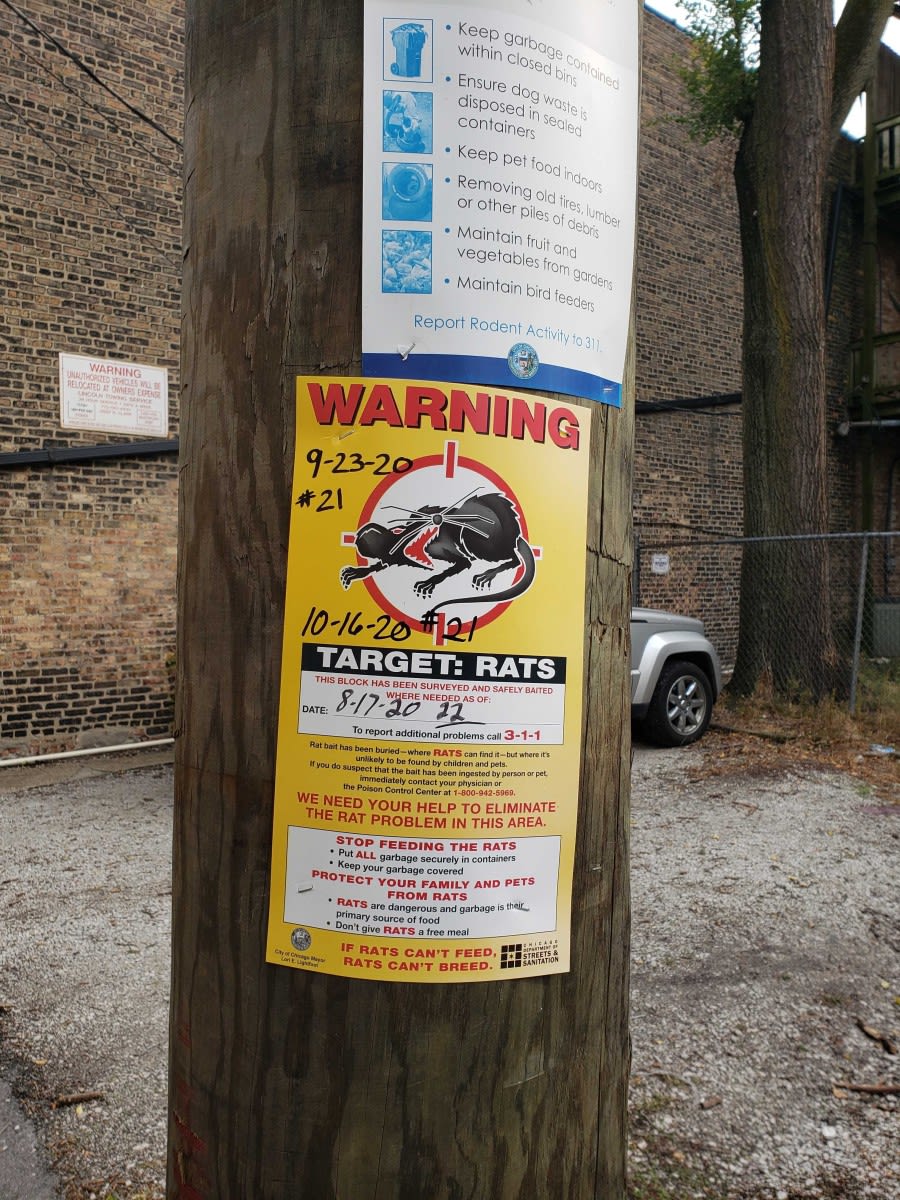

Image captured on strip of sidewalk adjacent to Pepperland and the focal tree.

Silver maples (Acer saccharinum) are one of a variety of maples that have a robust population in Chicago and the surrounding area. Joined by the Norway Maple, the Sugar Maple, and the Black Maple as the dominating maple varieties. Maple trees are fun. They are nearly ubiquitous across North America and very easy to spot. One would have to be a fool to mistake a maple tree for anything else, frankly. The characteristic v-shaped lobes, typically five but you will catch a 3-lobed maple leaf moving along every now and then, make them easy to identify, even for the most lackadaisical citizen scientist.

Enough about maples at large, let’s get back to highlighting the many quirks and features of the silver maple. The habitats they originally thrived in consisted mainly of swamps and floodplains. Something the Chicagoland area certainly wasn’t lacking before seeing rapid development. However, within urban habitats, the silver maple has found a steady home as an ornamental tree. There are some interesting contrasts between an urban silver maple and a forest silver maple. This contrast exists among most trees, wherein the stresses and stimuli associated with city trees often result in faster growth rates but ultimately shorter lifespans. The effect is quite dramatic. A forest silver maple can comfortably live beyond 100 years while an urban silver maple is capped, some would say, at around 40 years on average. My initial observations led me to believe that my tree was rather old, and its undeniable maturity could only confirm those suspicions. I wish I could employ some dendrochronological methods to extract the proper age of my tree. Oh, to be approximating the age of trees!

After careful consideration and numerous hours meditating by my tree in search of guidance, I have come to the conclusion that my beloved tree can be no other than the beloved silver maple of which we have spoken so dearly. This conclusion has been reached after close observation of the leaves, among other characteristics. The first clues as to the species of the tree will probably lie in its stature: it is a very tall tree with a “stout” trunk, which assumes a grey appearance. The bark, as the tree reaches maturity, becomes more flaky and brittle, as opposed to being smooth when young. As the tree gets older, there are ridges that develop across the bark, adding character and nooks for insects to utilize. Speaking of maturity, the silver maple sure can mature, reaching heights of almost 100 feet. Easily enough to eclipse an apartment building. If you can find a leaf on the ground, you will notice something striking besides the aggressive serrated edge: one side is a lush green while the other is a sullen silver-white. This is the giveaway of the silver maple; it’s all in the name--silver maple.

Silver maples also interact with their environment to a large extent via the process of hydraulic lift, a mechanism by which plant roots redistribute water across the soil. This passive process can occur in any direction although the term “hydraulic lift” may seem to restrict the direction to upward motion. Downward movement, when it occurs--which is largely dependent on the gradient--can enable the establishment of phreatophytic species. Phreatophytes are rife in areas where silver maples are, along water banks and generally moist places; their key characteristic being able to thrive deep into the ground, tapping into deep groundwater supplies where other species can’t make do. The process of hydraulic lift often reinvigorates the area around a maple. However, this effect is not felt on my tree. I would query that this is due to my tree’s status as an ornamental city tree. I wonder to what extent my tree exhibits hydraulic lift. Perhaps it is felt in the shrubbery and greenery nearby than in anything else more dramatic and apparent. Like many other maples and certain other ash trees, the samara fruit is the star of the show. Although one would hesitate to call it a star; samara is a dry fruit so its characteristics and even its status as a fruit is not as clearly perceived by passersby. Samara is interesting though. More than just a dry fruit, samara is also an indehiscent fruit--meaning the seed does not open when mature--equipped with an outer layer that almost acts like a set of wings when it floats down from the leaves. This winged feature has even become an endearing quality over time as a “helicopter.” I have memories as a schoolchild of playing with samara and watching it flitter down as I stood stupefied overhead on the playground set. Certain animals even make use of the fruit as sustenance. Squirrels and birds in particular are known to munch down on samara, while other animals confined to the ground try to make use of the bark instead. That’s one way to do it.

Image from backdoor of Pepperland, almost directly adjacent to tree.

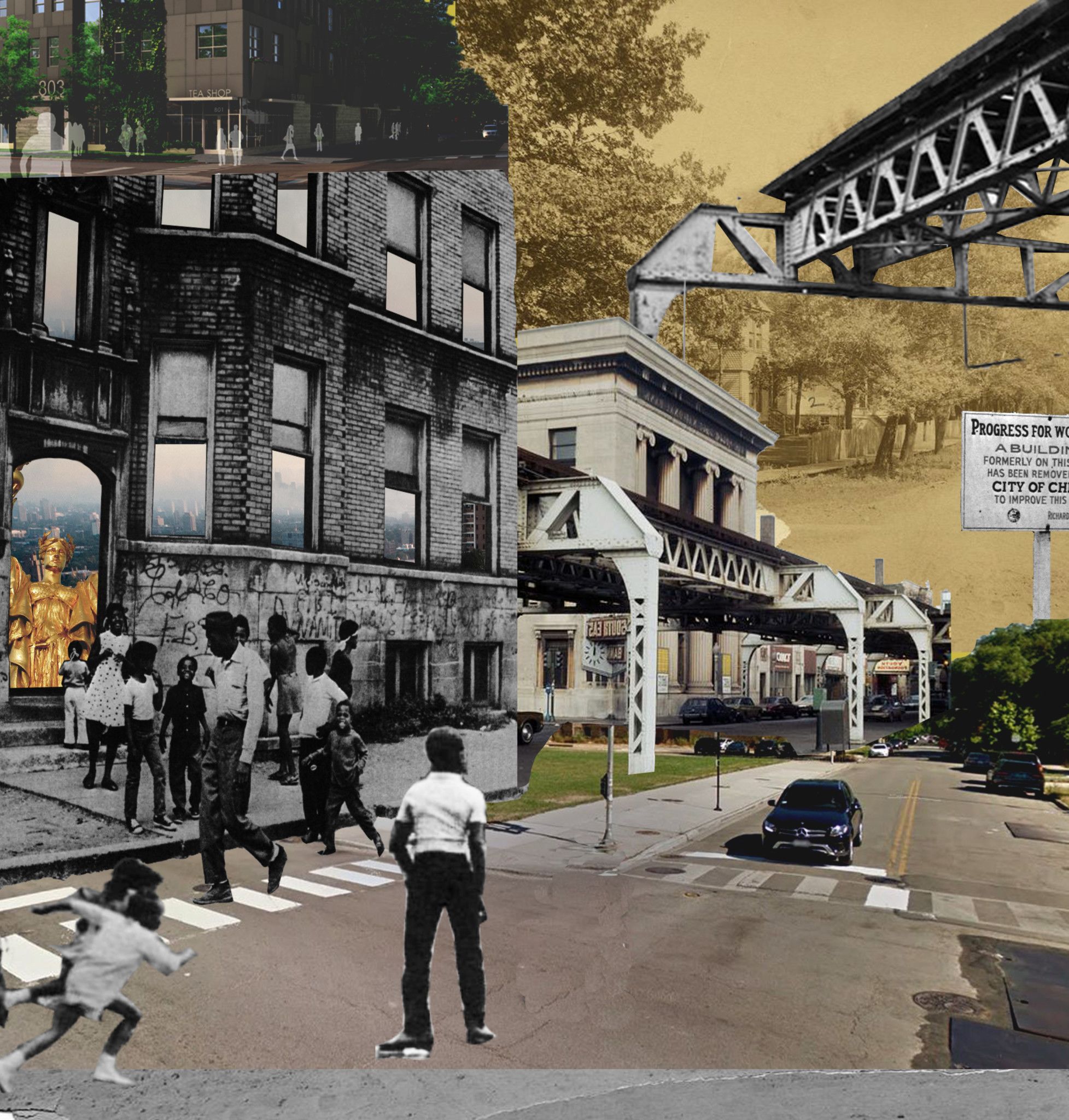

Moving beyond the cultural and historical significance of the silver maple itself, we must now pivot to the cultural and historical significance of the place inhabited by my particular silver maple. Walking east down 57th street, you will pass Harper Foods and come up to Powell's Books. Then, once turning right, you will find yourself in a peculiar location. After settling into your surroundings you will see walls develop around you. Four walls confine this tree and the field it is located on. Two of them are single-family homes, private residences. One of them is a street, S Harper Avenue. And the other is an apartment complex--the Pepperland. Standing in front of the tree facing south, the walls will be situated as such: flanking you on the left, ever-eastward toward the metra tracks, are three houses. These three houses comprise the 5709-5715 block on S Harper Avenue, almost obscured by this open field in which a shrub and some trees sit idle. In front of you, facing southward towards the Midway Plaisance, stand two more houses, 5717 and 5719 S Harper. Then behind you, facing north and away from these oh-so peculiar houses in this strange lot, stands the Pepperland. The Pepperland holds a unique place in Hyde Park history. This whole subsection of 57th street is quite interesting, actually. The most defining quality of this area would of course be the Illinois Central Railroad tracks, which were extended to this part of town around the year 1880, when this part of Chicago was still the Hyde Park township. These tracks originally ran along the ground, but in 1892 the city got involved with elevating the tracks south of 47th Street for improved efficiency and for the sake of fair-goers at the infamous World’s Fair, which took place just a stone’s throw away in Jackson Park. (Hansen & Hutchinson). Before there was Pepperland, there was Rosalie Flats, which derived its name from the street behind it (Rosalie Court, now Harper Avenue). Rosalie Flats sported a clubhouse for the Chicago Cycling Club in 1888, a time in which cycling was quickly gaining in popularity. It was one of the largest cycling clubs in the city at the time, even attracting some notable names in the field that have long fallen into obscurity. Just down the street, on the other side of the Illinois Central tracks, is where the 57th Street art colony once resided. The art colony was a curious thing, attracting artisans and craftsmen, among others, who were highly skilled but brought in low wages. Eventually, the rise of urban renewal in Hyde Park in the 1960s saw the demolition of the art colony. Today, the corporate headquarters of a sorority sit in its stead. (Hansen & Hutchinson). Not any sorority, though. This sorority was the first African American sorority in the country, Alpha Kappa Alpha, which had its second chapter at the University of Chicago. And I think that’s just the darnedest thing.

The historical significance of the Pepperland is not limited to just these general tidbits about Hyde Park/Chicago history. There is also some cultural significance tied to the University. You see, the Pepperland used to be where the UChicago ultimate frisbee frat took residence. This was an interesting era for ultimate frisbee at the University of Chicago, as an old Maroon article eloquently states, “at the U of C, frisbee is connected first, last, and always with partying hard and police cars headed for the Pepperland.” (Katz). The association between the Pepperland and the University of Chicago frisbee team lent it the nickname “frisbee frat,” which was its moniker until the building was bought by MAC properties in 2008. This is the building that makes the northern wall of the lot which contains my tree. This tree, then, sat here through it all, as the police cars headed toward the Pepperland and the frisbee kids partied on. I can imagine some of them coming out the back entrance that exits just a few feet away from my tree. Perhaps they were a little drunk, stumbling about a bit. Maybe they even stood at my tree for a second to gather their composure. And when they were all gone and the parties subsided, the tree remained. As it still does.

As far as silver maples go, this one near the corner of 57th Street and S Harper Avenue is very typical. Until it isn’t--but we’ll get to that. Starting with the bark: this tree is clearly mature. Its height and features leave no doubt in that fact..but what are these features? To begin, the bark is rather flakey and quite thin. There are also ridges that have developed, of which I have opined at length in my observations. These ridges further develop over time, creating little nooks and crevices that provide shelter for small animals. The nooks and ridges are all quite clear on my tree; it feels like a very distinct bark formation. Moving upwards to the leaves, this is where you can really confirm this tree’s status as a silver maple. Turning over a leaf, you can see the stark contrast between each side. One is a dark green, like any other leaf. The other is a milky silver--almost like some sort of imitation leaf. It is unmistakable. Furthermore, you will see the aggressive serrated edges of the leaf, which are more violent and apparent than in other maple varieties. However, there are still some atypical quirks for my tree. Mainly, it did not develop the typical shape that a forest silver maple might assume. This I would say is largely a result of the urban environment that no doubt played a dominant role in the development of this tree. It is clear that the presence of the Pepperland and the subsequent blocking of sunlight from that side of the tree has contributed to the appearance and character of the tree.

57th Street Art Colony, University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center.

57th Street Art Colony, University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center.

So, where is this greaty nearby? Many a UChicago student would probably--not so arbitrarily--set the limit of their scope to E Hyde Park Blvd (51st Street) to the North, S Cottage Grove Ave to the west, 61st Street to the south, and the Lake to the east. However, I wholly reject this idea. And I happen to spend a lot of time in the surrounding area, my assigned school for the Neighborhood Schools Program (NSP) is on 65th and Ellis--Wadsworth Elementary School, a damn fine institution.

(Image source: James Wadsworth Elementary School).

In the spirit of what has been said so far, the limits I have decided for my Great Nearby extend to E Hyde Park Blvd to the north, Martin Luther King Dr. on the west 65th Street to the south, and the Lake to the east, . Within these limits, boundless history can be found by analyzing the land use patterns, ecological context, and current conditions, so let's get into it.

Taking Native Land:

The History of Chicago before it was Chicago & how the first people kept the land.

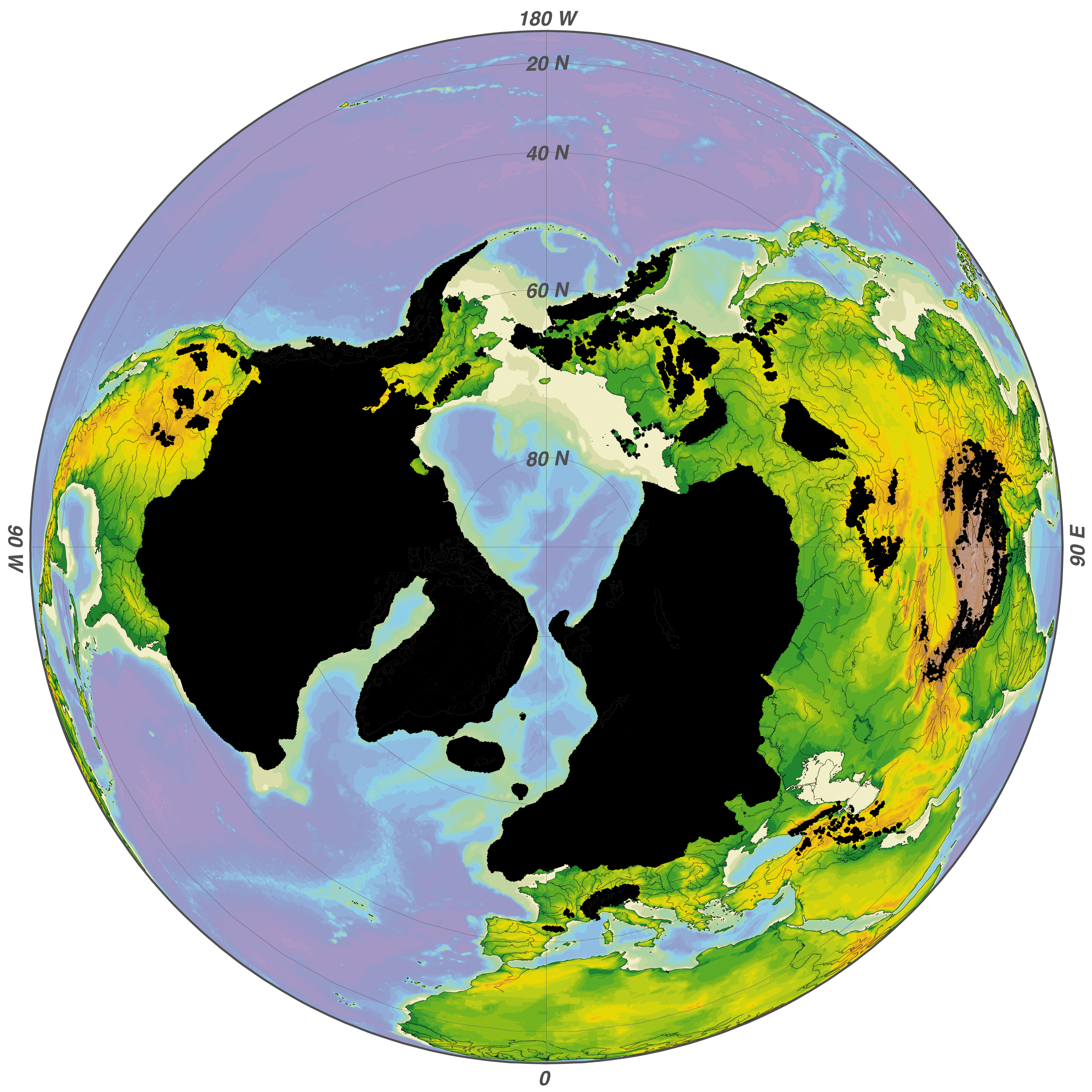

Many thousands of years ago, the first people ventured forth onto the western coast of North America. At the time, the area that would become Chicago was still covered by glaciations. The Wisconsin advance--the last major advance of the Ice Age--was still pronounced and unmoving, though it's time would come some millennia down the road.

The melt-water from these subsiding glaciers would go on to form the waters of Lake Michigan and the accompanying Great Lakes, which came largely from the Laurentide Ice Sheet that loomed large--very large! At certain points it exceeded 3 miles of thickness. That's intense.

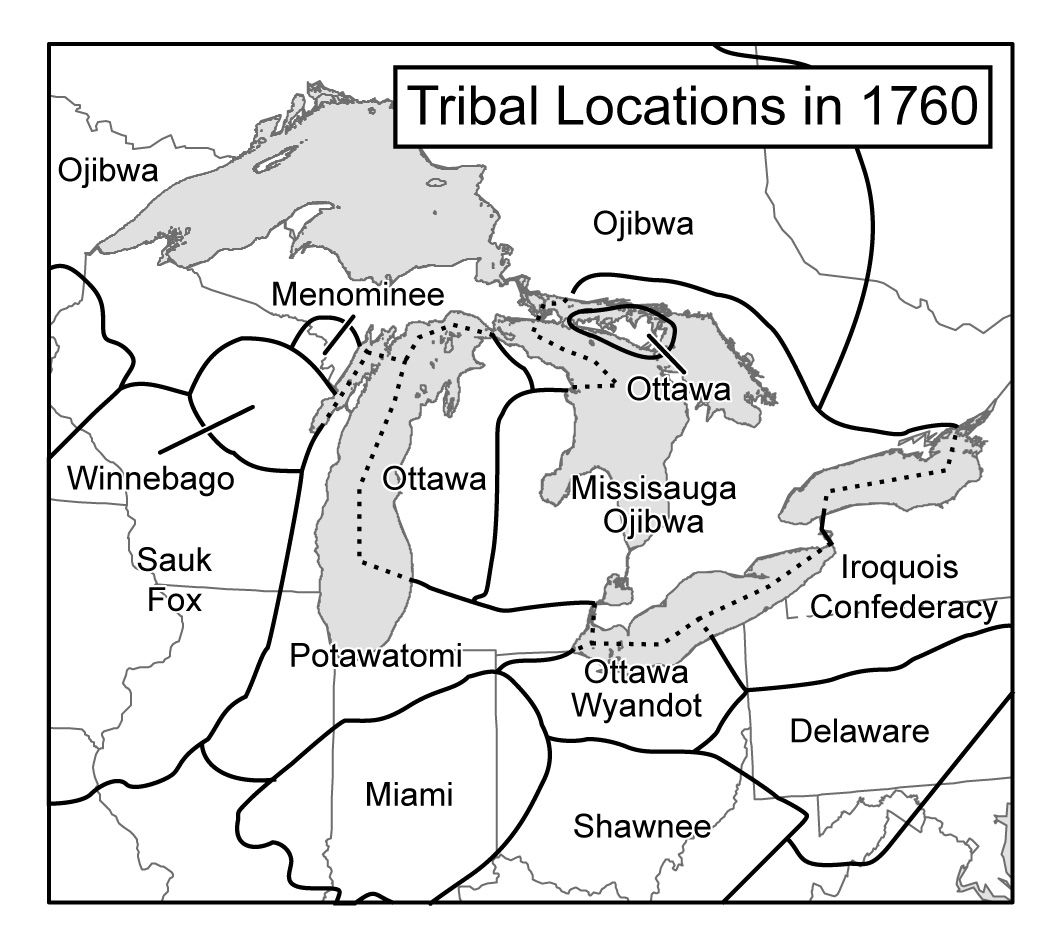

There were numerous distinct indigenous tribes living in this region, but some of the more notable Great Lakes tribes include: the Potawatomi, the Miami, the Fox, the Ojibwe, the Menominee, and the Illinois. There were extensive trade routes among them, and some were later adapted for roadways in Chicago.

One of the first documented interactions between the Natives in this region and Europeans happened in 1673, when Marquette and Jolliet were passing through. This was amidst a four-month expedition to explore the area around the Mississippi River. Marquette was a Jesuit Father while his chum Jolliet was a fur-trader, they were a fun bunch.

Image Source: Pictorial History of Michigan: The Early Years, George S. May, 1967.

At the time, they noted the presence of the Miami. Among Great Lakes tribes, the Miami were a meeker bunch, numbering only 4,000 of some 100,000 natives likely residing in the region.

The Miami would be displaced, however, when the Iroquois Confederacy drove into the Great Lakes region in a bid to monopolize the fur trade, playing Europeans on a smaller field it would seem.

This increased aggression by the Iroquois would lead to the Potawatomi, once inhabiting the lower peninsula of Michigan, to move Westward toward Illinois--displacing the meek Miami as the Iroquois had done to them. The Miami moved southeast into Indiana, getting the sour end of the deal at every step, so it goes.

There was warring and moving around among tribes, but boundaries were largely respected. Across all tribes, one thing held constant: no single man had the vanity, or the ability, to try and concentrate and accumulate land under his name. Instead, distinct tribes embedded with millennia of tradition and persistence would come to occupy the land, and in that way “own” it. The tribes would not only occupy the land, they would also transform it.

As Aplet and Cole state in their 2010 article, The Trouble with Naturalness, “indigenous people burned for many reasons, in different frequencies, intensities, locations, and seasons.” The impact of their burning, too, was variable. In some cases, it completely changed landscapes. In others, it shaped a landscape not entirely perturbed.

The use of these controlled fires to modify the landscape was very widespread. Fire is a universal tool after all. The landscapes that we--the second people--came to view as pristine and untouched were actually the very opposite. They were the culmination of generations of land maintenance and careful management by the first people. When the Europeans came forth and effaced the Native American influence, this proved a radical change to how the land had hitherto been maintained.

As Western norms set in and the native cultures that originally existed in their place were supplanted, fire suppression became law. The land was abused by the second people; they took advantage of the land they inherited because it was novel to them and there was so much of it. There are now conscious efforts to utilize the same techniques we once made drove out.

As we conclude this section on the native people of the Chicago region, we must acknowledge their contributions in the formation of the prairie. The two main conditions that allowed for the formation of the prairies were periods of drought and fire. The periods of drought came in part because of the Rocky Mountains overhead, which created a “rain shadow” that subsequently lowered rates of precipitation for the land that would become the prairie. Intersperse millennia of controlled burns and fires that terraformed the landscape, and you have all the conditions for prairies and grasslands to develop. And boy did they.

The Oregon Encyclopedia

The Oregon Encyclopedia

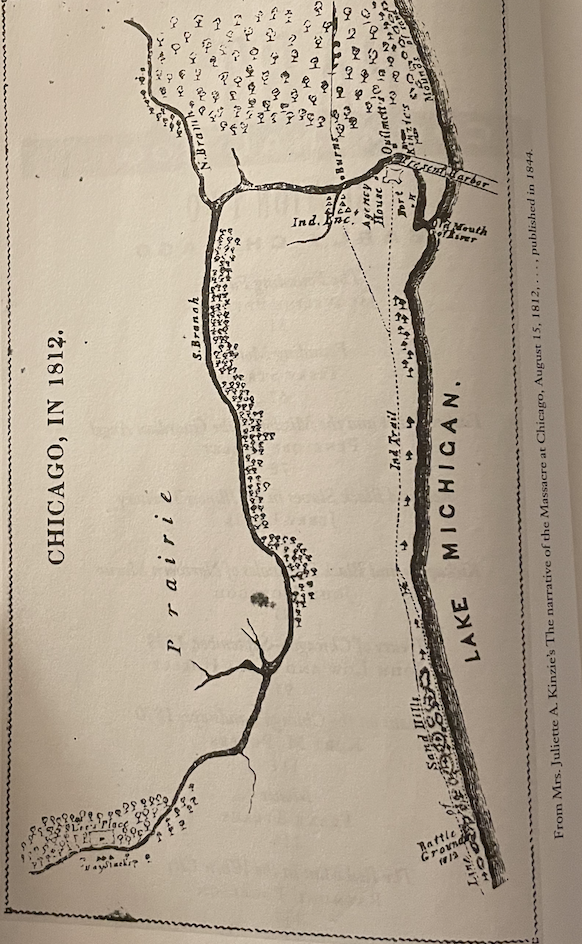

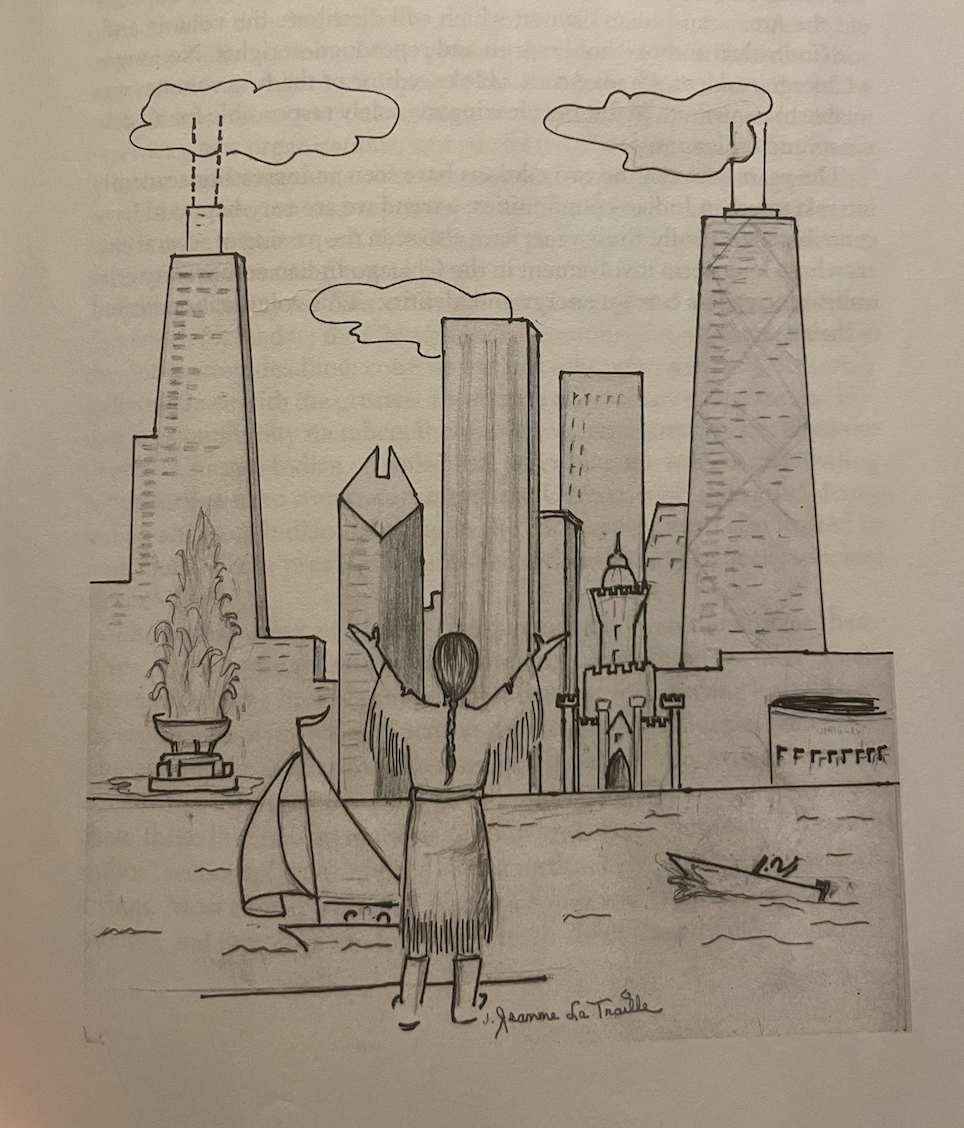

Image Source: Native Chicago by Terry Strauss, Illustrations by Maryanne Humphrey

Image Source: Native Chicago by Terry Strauss, Illustrations by Maryanne Humphrey

Reflection Week 2 - Ingo Kowarik & the Four Natures.

It is rather difficult to find the four natures existing in proximity to each other. Let us remind ourselves of the hierarchy of the four natures (as set forth by Ingo Kowarik) before we continue. First, we have remnants of pristine ecosystems. Then, there are rural cultural landscapes--the second nature. Next, urban green spaces, usually controlled to some extent--our third nature. And finally, nature of the fourth kind manifests as novel urban green space on vacant lots or other urban sites.

Within Chicago proper, it can be difficult to find good examples of the different kinds of natures. I wanted to try to challenge myself in finding the four natures in relative proximity all within the borders of Chicago. For this task, I head to the northwest side of Chicago. I don’t spend a lot of time on the north side of Chicago; I have an aversion to it. When I do, however, it is usually in Rogers Park or Edgewater, straddling to the pretty blue Lake. I have been to the northwest side once or twice though, in the Albany Park area or thereabouts. Something that really struck me about that area when I was passing through was the seeming inclusion of wooded areas, as in actual woods. I was fascinated by the idea of woods in Chicago, we don’t have much of that in Hyde Park.

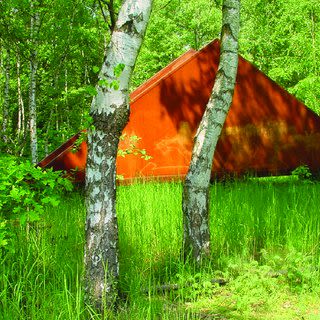

For first nature, I chose the girthy (for lack of a better term) LaBagh Woods. I would imagine that this area was preserved in the early years of Chicago’s planning. It doesn’t seem like something that could just arise artificially. And after some light research, I have mostly confirmed these assumptions. The preserve was named after Ella LaBagh, who after seeing lumbermen cutting down trees in the late 19th century, devoted herself tirelessly to campaigning for the trees. The area has some second nature, too. It straddles the north branch of the Chicago River and extends quite a bit, so over the course of its progression you will see some wetlands and savannahs, which serve as our representation for second nature. It is quite the peculiar thing, for Chicago at least! Moving down along the river, we needn’t go far before coming across Montrose Cemetery and Crematorium, our representative for the third nature. There are also some parks managed by the Chicago Park District. You can never get too far from those.

For fourth nature, you must move south to the South Deering community area. South Deering is an interesting place. 80% of it is zoned as industrial, natural wetlands, or parks. Much of that is dominated by Lake Calumet. The area was largely industrial at one point, and remnants of industry can still be perceived, perhaps most notably in how it affected the environment. And of course the inclusion of the wetlands and swamps nearby shows us some second nature, too. I would imagine that the average Chicagoan is quite perturbed by most manifestations of fourth nature. They see it in vacant lots, in abandoned industrial sites, and other places that might be perceived as scary or unpleasant. The pristine aspect of these environments is also not appreciated by the general public. Whereas something like third nature may be more appreciated or doted on by the average Chicagoan. People like things that are controlled and maintained. First and second nature in Chicago are hard to come by, and because of that, those spaces are fetishized, and a vested interest in preserving those space takes hold. We have the sense about us now to try and save the pristine parts of our landscape we have left, but still more they feel under appreciated by the larger audience.

Image Source: Cook County Forest Preserves, Photographer Michael Courier

Image Source: Cook County Forest Preserves, Photographer Michael Courier

Photo by Ingo Kowarik

Photo by Ingo Kowarik

Image of Ella LaBagh & Company; University of Illinois CARLI Digital Collections.

Image of Ella LaBagh & Company; University of Illinois CARLI Digital Collections.

Credit: John Mark Hansen, Chicago Studies, University of Chicago.

Credit: John Mark Hansen, Chicago Studies, University of Chicago.

The Washington Park Subdivision

The forgotten part of our great nearby, its history, & some notes on ecology.

Highlighted in purple you can see the vacant lots that are present throughout the space. The two thoroughfares highlighted in yellow are S Martin Luther King Dr. and S Cottage Grove Ave. The green line rapid-transit tracks are highlighted in green. Outlined in red you can find impervious surfaces: things like parking lots that attract heat and don't retain water. Most of the zoning is residential.

Image Source: Google Earth; alterations made by author.

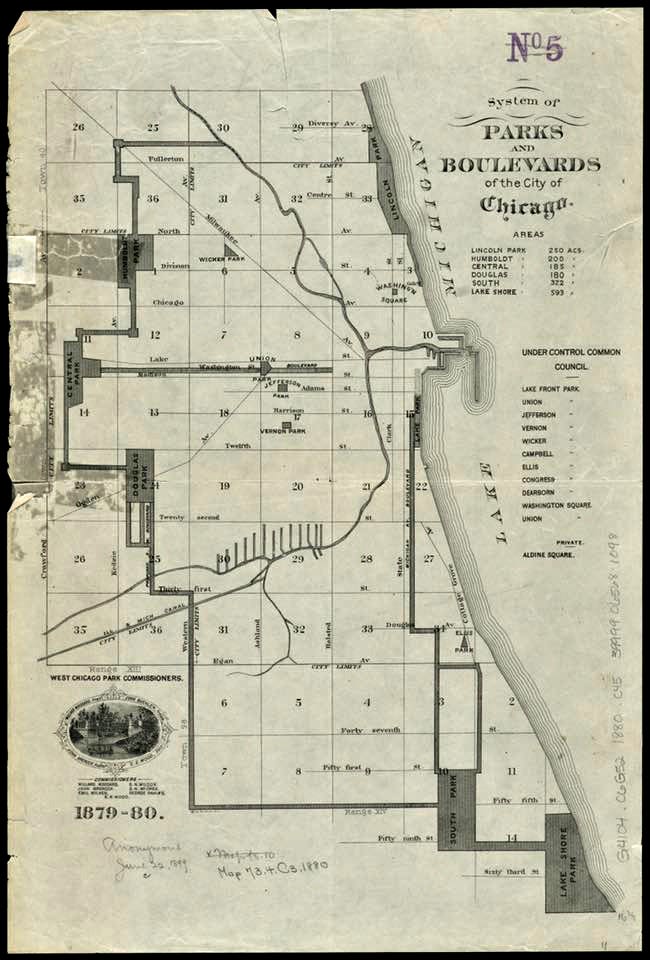

The Washington Park Subdivision makes up a formidable section of my defined Great Nearby. The subdivision is bounded by Martin Luther King Dr. (formerly South Park Avenue.) on the west, Washington park to the north, Cottage Grove to the east, and 63rd Street to the south. The Washington Park Subdivision has had quite a colorful history. First, there was the Washington Park Race Track, a horse-racing venue that attracted some of the city's most elite, located on the corner of 61st Street and S. Cottage Grove Avenue. The race track took up roughly ⅔ of the subdivision.

Image Source: Henry R. Worthington, [by] Rand McNally & Co.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons via user:TonyTheTiger using US Government provided TIGER tool.

Image Source: Chicago History Museum . [C.N.Greig & Co., circa 1900].

A look at an 1884 handbook from the Washington Park Club shows a preponderance of significant names: some Kimballs, Augustus Quackenboss (rad name, of no significance), Martin A. Ryerson (of the famed Ryerson Laboratory), and Charles Yerkes Jr. (of Yerkes Observatory fame; also developed the Chicago rapid-transit system as well as the London underground.). The club was a dashing success before being demolished in 1905 when an anti-gambling mayor rolled in.

Image Source: Accessed via Boston Public Library Leventhal Map Collection. Created by Chicago (Ill.). West Chicago Park Commissioners.

![Image Source: Henry R. Worthington, [by] Rand McNally & Co.](./assets/ndI509wtFE/screen-shot-2021-11-01-at-3-57-35-pm-1082x846.png)

University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center. Depicting 62nd Street in Woodlawn, adjacent to what seems to be the Illinois Central Railroad Tracks.

University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center. Depicting 62nd Street in Woodlawn, adjacent to what seems to be the Illinois Central Railroad Tracks.

Race tracks have faced increasing scrutiny from the environmentally-conscious because of the damage that comes with them. They are very large in size and see a lot of animal waste get deposited; not only that, but they are also very harsh to the land. Needless to say, the Washington Park Club certainly had an impact on the land that now sits here.

Walking around, however, it is hard to tell if the rough spots of the area--frequent vacant lots and underutilized land, a noticeable lack of trees--are the cause of the former race track--now over 100 years effaced--or from the environmental racism that stemmed from the racial covenants and white violence that was prevalent in the era. Something I noticed while walking around is how many young trees line the streets. Well-established and mature trees are more seldom and hard to come by. I wonder how many, if any, of these trees are the result of Mayor Richard Daley's initiative to plant 500,000 trees.

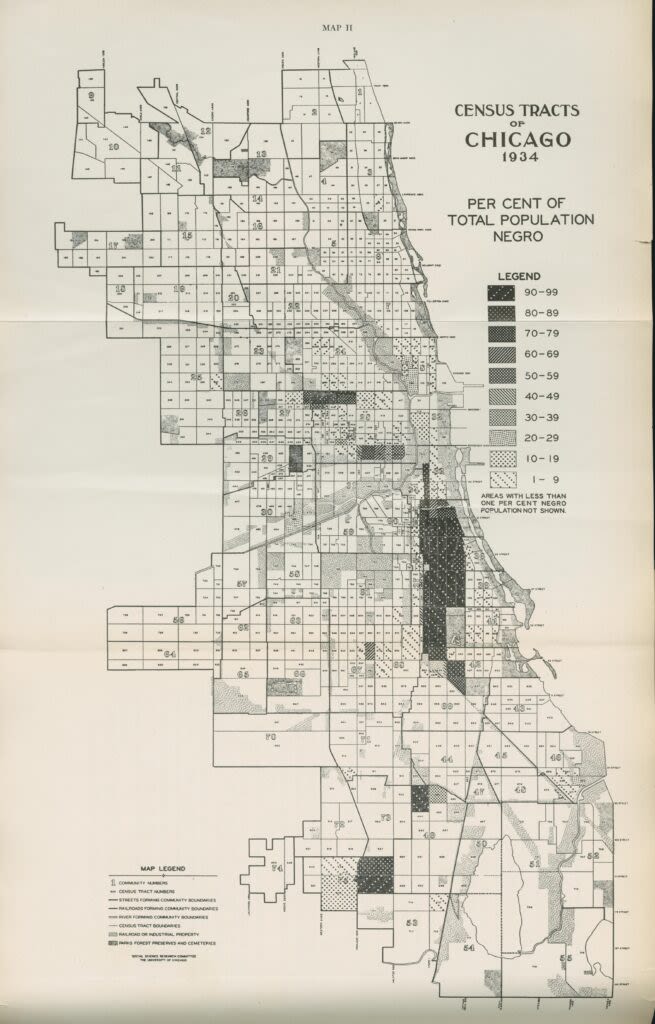

Racially restrictive covenants and the threat of racial violence kept the area white for a time. These restrictive covenants were so woven into the system that oftentimes homeowners were unaware that they were enforcing and abiding by them. By 1938, racial covenants restricted over 80% of the city, saving just the “black belt” that had formed along State Street for African American residents. It got to the point where there were 50,000 African Americans that simply couldn’t find housing in the narrow corridor in which they were permitted to live. Not only was the housing squalid and dismal, but it was deftly overpriced. A black family of 9 would in all likelihood be paying more for accommodations than a white family of 4, and unequal accommodations at that.

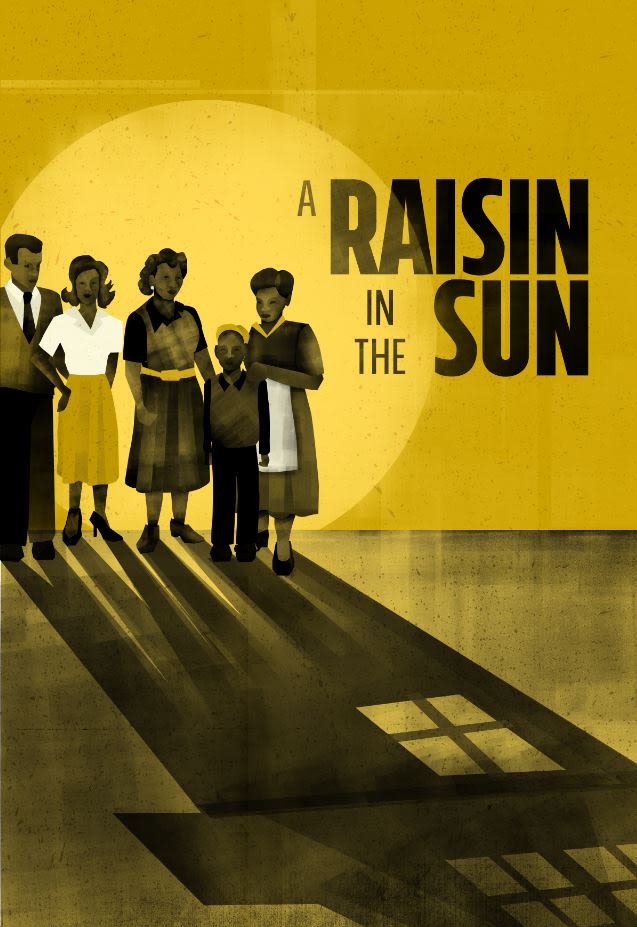

This all came to a head when, in 1938, Carl Hansberry tried to buy a home for his family. The ensuing events would serve as inspiration for the play A Raisin in the Sun. By 1940, only 3 black families would live in the Washington Park Subdivision. The University of Chicago took notice of the changes to come, though. It was widely acknowledged that the Washington Park Subdivision acted as a buffer between Woodlawn, then a predominantly white neighborhood, and the black belt that lay beyond. It was with this in mind that the University of Chicago allocated funds for the Woodlawn Property Owners Association, a group of white businessmen enforcing a covenant on the area. The efforts of the University were for naught, though. Today, the Washington Park Subdivision and Woodlawn to the east are predominantly African American, much to the chagrin of the University.

Image Credits - Ireashia Bennett, Ellen Hao, South Side Weekly.

Image Credits - Ireashia Bennett, Ellen Hao, South Side Weekly.

Just south of the Washington Park Subdivision, from 64th Street to 67th Street along King Drive, you will come across Parkway Gardens Homes, a low-income housing development that has a storied history, and a colorful reputation to boot. Constructed between 1950 and 1955, Parkway Gardens came at a time when these racially restrictive covenants were still very real. Not only did they provide adequate housing, but it was also the city’s first public housing project to be cooperatively owned by its residents. Everything started out alright. Even Michelle Obama’s family lived there for a time. Unfortunately, the cooperative is no more. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) seized control of the buildings in the 1970s, and in the 1980s it would fall into private hands where it remains to this day. Related Midwest, the management company that took over in 2013 and pumped over $40,000,000 into the complex, is now looking to sell the property. Hopefully it goes to a more conscientious management group. That being said, I could certainly feel some of the recent investments when I myself went wandering there. The grounds could certainly use more proper maintenance; the trees, though they exist in quantities greater than I anticipated, still come nowhere near forming a proper canopy. There were about 8-15 trees in the four courtyards I inspected, bounded on all sides by buildings. The trees are of varying species and maturity; some have been there decades, it would seem. Others maybe just a few years. All of them look markedly different from those steadfastly maintained on the University of Chicago campus. Among the trees I was able to identify, there were many honey locusts, some silver maples, an elm or two, and what I am almost certain was an ash tree--I mean in this time! I have not been able to find if the Parkway Gardens complex has air conditioning; many public housing sites do not. I imagine a proper tree canopy would do some good in the summer. My family went two summers without AC in the muggy Carolina heat during our struggle years. That is no way to live! There were also some planters at the entrances to the property, a nice sprig of color to contrast with the otherwise drab looking buildings.

Image Source: Chicago Sun-Times.

Image Source: Chicago Sun-Times.

Although I must say, I was quite pleased with the architecture of them, it was more so the shading that was unpleasant. There were some nice accents--it seemed quite classy for public housing. I also like that the buildings don’t get too big. The grass, however, seemed to be in bad condition. I am not sure who keeps up with the lawn maintenance, but I would imagine it is not Related Midwest. Parkway Gardens also sits directly adjacent to a railyard.

Image Source: Newberry Library, Digital Collections.

Image Source: Newberry Library, Digital Collections.

Image Source: Library of Congress, Broadway theatrical release poster.

Image Source: Library of Congress, Broadway theatrical release poster.

Credit of the Chicago Sun-Times.

Credit of the Chicago Sun-Times.

Image Source: Chicago Neighborhood Development Awards.

Image Source: Chicago Neighborhood Development Awards.

Observational Notes From Weeks 2 - 4 - 7 - 8 - 10

I like to ride my hands down the bark, fingers in the grooves moving gently. As I do this I notice something: the bark rides up and off the tree a lot. I look closer, trying to see what different processes are supported or hindered by the different goings-on of the bark. Then I see something--my first insect! I had been trying long and hard to find life on my tree, but up until now to no avail. I’d imagine most of the insects that use this tree utilize these little crevices under the bark. It was interesting trying to track ants as they moved from one crack to another.

Much of the base of the tree is thoroughly entrenched in the ground. I was not able to make out more than some moss, and the fact that the base of the tree seems to be less firm and more malleable than the mid-section. It felt almost soft; like I could push the tree inward if I really wanted to.

Another focus of mine this past week was the environment around my tree. First, I thought about the built environment. The tree sits adjacent to the Metra Electric tracks as I discussed last week, but the tracks are obscured by a house. I made a little diagram to illustrate the urban environment of my tree. It is flanked by five houses and the Pepperland complex. They make a little wall of sorts around my tree. They confine the space and give it a boundary. The field in which the tree lies is expanded a little bit below. There are some trees that color the area--different kinds of trees, both coniferous and deciduous trees. Something about the kinds of trees that are here and the way they are arranged leads me to believe that the trees were placed here by humans and did not arise naturally. My concept of what is natural is at this point thoroughly eroded, so I will not comment further on that. Another thing that leads me to this belief is the age of the structures around the building. I could not find details for the houses, but based on the environment around the houses, and building off of my previous discovery that the Pepperland dates back to the 1880s, I would have to imagine that most of them date to the early days of a rebuilt Chicago. That certainly flows with the idea that these trees were placed by man. It does feel like a very manicured space, but I am learning to appreciate and accept that as nature, too.

I see..the leaves! For once, I have finally taken a step back to examine the leaves. I’ve gotten so carried away by the bark. It really is captivating bark; it gets me in a trance. But now that I see the leaves, after some direction, It all becomes much more clear to me. After examining some leaves that had fallen to the ground, it became clear to me the hue of the underside of the leaf was very different than its greener counterpart. I don’t know what more you can say about this tree.

I see..woah can it be..a squirrel! That's right, I finally caught a squirrel. Not in any meaningful way, though. And by that I mean branch-interaction. Only a few moments were spared no more than 3 meters up the tree before erratically running back down. I followed squirrel to see what he would do next, at which point friend scurried to this small strip of land between the Pepperland/adjoining lot and the Illinois Central tracks. There are some small and gangly trees in this section, but they look like maybe that is how they are supposed to be. I don't spend too much time examining this area, bounded by a tall chain-linked fence that creates quite the barrier, probably for good reason.

I saw quite a few twigs and small branches on the ground. There was quite the storm recently, so. I was expecting to see some debris. I was expecting to see a little more, hoping to, honestly. It would be nice to document some tree limbs falling, but it was just a small blip. Quite a resilient tree. I can also see some animal feces nearby very close to the base of the tree, seemingly from a very large dog. Within 3 meters. I wonder if this is a stranger dog or if it lives in one of the adjoining residential properties. After seeing some of the fallen twigs, I picked one up to crack it just for fun. A slight musky smell leaked out. I t was nice to feel the wood. I do enjoy spending time with trees. I wonder if animals have an opinion on this smell. It doesn't seem like maples are particularly tasty to most animals. What is the effect of the odor on this? Something to chew on.

This time around I saw a cat—black. They were prowling around the area, even rubbing up against my tree a bit in my time observing her (tree). I have not yet seen a cat strutting around the tree—I have seen dogs on the adjacent sidewalk before, and even that steaming pile of canine excrement in weeks past. Also saw a bird bounce around the branches before flying off.

I wonder where this cat is...

I tried playing around with the dirt this time. Dirt is awfully nice to play with, and you can learn a lot about a tree from the soil it rests in. I was quite impressed by the quality of the soil. It felt very rich and moist, very dark as well. I imagine the grounds are maintained very well by the families that reside directly adjacent to the space. I see a lot of leaves still inhabiting my tree. Most of the litter that sits on the ground is not of my tree, but has instead drifted to the space from other trees.

I see a familiar hole, a large one on the south facing side of the tree. This trip, I decided to put a spotlight on said hole. I spent the entirety of my trip—about 20-30 minutes—watching the hole. I always wanted to take a closer look, to examine it in full. It was one of the features of the tree that first struck me, and it is something that I have used as a bit of a benchmark throughout my observation periods.

So I sat and I watched. Many minutes passed, and many a bird chirped nearby. I am starting to see the nests that take up other trees as leaves fall, perhaps the lack of leaves amplifies their calls. The sitting continues—and nothing. I sit and I sit, watch and watch, but nothing is happening. The most noteworthy thing I am able to perceive is an inhabitant of the Pepperland, who I can make out through a window, but alas nothing else.

As the seasons marched on, you could certainly feel the reverberations of the cold weather on our surroundings. I was given the note to check back on the soil conditions as the climate started to turn, so I went back armed with a spoon to see what was up.

The soil certainly seemed to have hardened since my last dig. Last time, I was armed with just my hands. But alas for this trip I needed something more, though access to a shovel was not certain for me.

Reflection Week 4 - Citizen Science & Spending Time with Nature.

The nature of cities has us always shuffling about from one location to another.

So rarely, especially in our particular great nearby, do people take a second to observe and engage with the nature and wildlife around them. This disconnect between us and the urban environment is part of a larger disconnect between cities and nature that isn’t necessarily warranted. There is a lot we can learn and see from spending time with trees or following squirrels. You start to see patterns, and how you fit into the ecosystem with urban wildlife. These patterns that you will observe, when in connection with one of the cited larger scientific projects, can provide meaningful data points for future reference.

Another meaningful nature project to embark, I propose, would involve close observation of grass/lawns as they differ across our great nearby. I have noticed, even seemingly within the parameters of campus, differences among University maintained lawns and those maintained by Chicago Park Districts and private residents. There is quite the spectrum between Hyde Park, Woodlawn, Kenwood, and Washington Park. The impact of this on the participant would be two-fold. For one, it would give some perspective to the citizen scientists, who in our case likely never leaves the Hyde Park bubble. For another, you could log the conditions of lawns for posterity, perhaps to one day be used to see how the drought of last Spring affected Chicago greenery. Or perhaps it could be a part of a larger longitudinal observation project. Perhaps if the impact of climate change continues to be felt--not really a perhaps, I suppose-- there will be some more apparent effects. What are the different species of grass? Do different species react differently to the drought conditions that we experienced in the Spring, and might experience in the future? The suburban town of Joliet has had to borrow water from Lake Michigan because its aquifers are running dry. Is this a common theme throughout Chicagoland? What correlation does this have, if any with the quality of the grass/greenery? There is a lot to pick up from grass. It can tell many stories.

Citizen science is important, and every bit as valid as science science. Many positives would flow from an increase in citizen science. First, it would better connect people with nature. It is often said that there are a million miracles behind a flower. Once you spend some time in nature, it is almost hard to not feel some sort of connection. At least for most sane and law-abiding people. And as voting-age citizens, our opinions and perceptions end up being pretty important, for better or worse. After engaging with the readings and activities for class, I feel inspired to be a more conscious citizen scientist. Even the little things can go a long way.

Reflection Week 5 - Talking Opossum

I have made a point to visit my tree at varying times throughout the day and into the night. I don’t often log my night trips because they are impromptu and brief, usually coming as part of a stress-relieving night walk. However, these night time excursions have led to some interesting encounters. Particularly with the elusive urban animal Didelphis virginiana, the opossum. In the United States and Canada, only one opossum species persists--the Virginia opossum I have had two encounters with an opossum in the past few weeks since adopting my tree, which is far more frequent than my usual level of interaction. Neither of these encounters were particularly close to my tree, nor were they especially notable. Each opossum got to within 10 meters of me, hardly perceiving my presence and dashing from street to alley. These encounters, though brief and transient, were enough to inspire some research into opossums and how their presence is felt in the urban environment. Opossums are one of those things you never really think about. Most of our interactions with them are characterized by avoiding them. In writing this, I consulted with some friends who said they had never even seen an opossum. Is that by chance or by design? Well, opossums are nocturnal, so it would make well enough sense why they keep at bay. But what do we think about opossums? Our perception of opossums seems to be largely colored by how they have adapted to the human built environment.

Distribution of the Virginia Opossum | Image Source: The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Distribution of the Virginia Opossum | Image Source: The Canadian Encyclopedia.

The Virginia opossum is found as far north as Canada, but opossums originated in South America. Their ability to thrive in an urban environment is why they have been able to proliferate so successfully up north, but it has also tainted their reputation. Now, we see opossums as fiends and nuisances, which is not a wholly unfair perception since a study in Oregon found that 9% of an opossum’s diet was garbage while another 9% was pet food. Is it fair to view them as pests in light of this? Should we really shame the opossum for having adapted to its environment so well? I think not. Another aspect of the opossum I would like to touch on is just how great at hustling they are. Opossums are not creatures that make their own shelters; instead, they rely on their resourcefulness to find and commandeer shelter in their urban environment. This often manifests itself as a built structure or a tree. Opossums love trees--that is something I was surprised to learn in preparing this reflection. It makes sense, I suppose. Opossums live in urban areas that are typically near wooded areas. Where else would they reside if not on trees? Perhaps in your attic, or in a hollowed out log somewhere. Leave it to the opossum to find a habitat. The little hustlers. I have never consciously observed the nest of an opossum, especially not when that nest happens to be in a tree, but now I am always on the lookout. I have heard opossum meat is might tasty, too.

On my walks, I have also noticed those infamous “DO N OT FEED THE RATS!” posters that have swarmed Chicago allies just as the mighty rat has. It has made me start to wonder: are rats really out of control? Should we really be as concerned about rats as we are? They don’t seem to care as much in New York and that’s a mostly functioning city. Rats aren’t the only pests in our urban environment, as the opossum has shown us. Why is it that we single out rats as uniquely bad? In this way, humans are certainly acting as the drivers. Something else I have noticed about Chicago is the colorful lawns of the residents that live here. In the suburban environment I am familiar with, it is common to see those placid and ecologically depressing lawns--the over-maintained grass. Here, people take great pride in seemingly making their lawn as chaotic as possible. Many different plants take up space, but very rarely do you see suburban-esque lawns in the city. I wonder how the soil of a frenzied Chicago lawn would compare to the soil of an arid suburban lawn. I wonder if the addition of non-grass greenery provides more sustenance for animals and enables an ecosystem. The prompt we were provided with touches on the topic of birds. Birds are a species that don’t often occupy my mind. I will try to pay more attention in the coming weeks to how birds interact with my great nearby, and also perhaps to what mechanisms we have employed to enable or harm the proliferation of birds. My mom was very scared of birds when I was a child.

Image Source: Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

Image Source: Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

Image Source: USA Today.

Image Source: USA Today.

Reflection Week 6 - University Grounds & Beyond

The most stark differences will probably be between University-maintained property and the lands maintained by the Chicago Park District

. I have often noticed on my walks between north and south campus, the clear disparity between the Quad and the Midway in terms of overall aesthetic quality. My friends and I often deride the University’s strict maintenance of the lands, because what is there to complain about when everything is taken care of so stringently? Part of me has to wonder the extent to which everything is maintained--even extending beyond campus. What mechanisms of altered hydrology are employed on the Quad that are not so performed on the Midway? It would seem that the Quad has more impervious surfaces than the quad. I might, at first, take this to mean that the Quad would be worse off for it, but that does not seem to be the case. At what point do impervious surfaces become negligent, or at least not proper determinants for the land? My tree is located on a lot of sorts and is right next to Jackson Park. However, it is also right next to the Illinois Central Railroad tracks. Does Jackson Park’s presence affect my tree at all? Would that effect be negated by the railroad tracks that sit even closer?

Image Source: University of Chicago, Office of Safety & Security.

Image Source: University of Chicago, Office of Safety & Security.

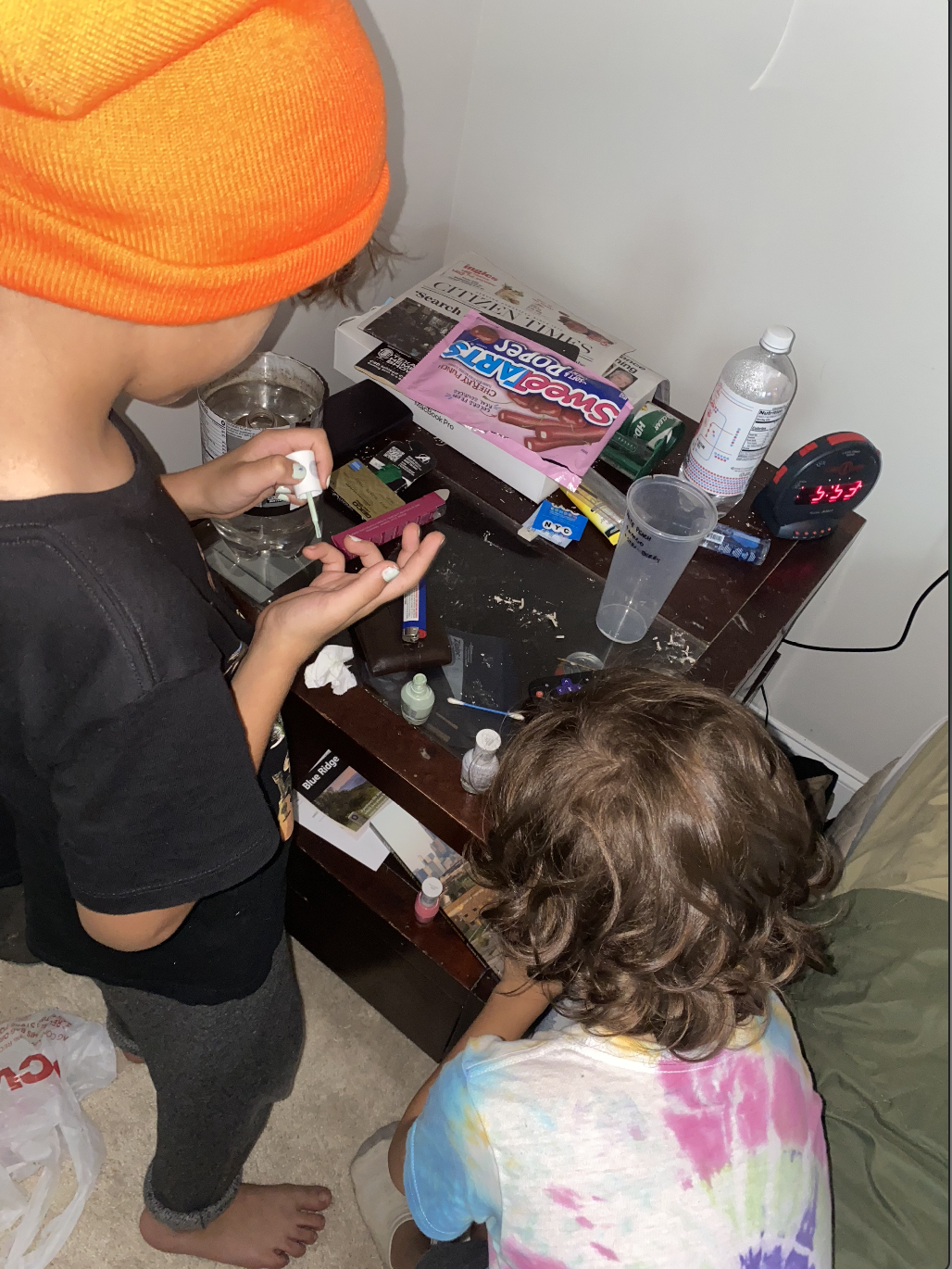

In his strange little article, Ralph references Edith Cobb and her book Ecology of Imagination. This is a particularly interesting entry because of its focus on children and childhood. Since I helped raise four younger brothers, I have always been particularly attuned to the needs, wants, and presence of children. Cobb goes on to talk about what kind of experience nature is for a child: “a sheer sensory experience.”

Image created by author.

Image created by author.

This ties into Leopold’s thesis in the Land Ethic, which basically implores you to take a more communal approach to existing in a space. You are existing in that space not in a vacuum, but with grass, and flowers, and trees. Children are part of this space, too. The interactions they have with nature in this formative stage, as we mentioned in class, carries over when they are voting-age adults. The children of today are the voters of tomorrow. Their appreciation of nature is just as important as ours. All around is in our Great Nearby, there are different ways of seeing what we see with our boring, non-plastic brains. From a child’s perspective, you can unlock a whole world of...worlds. I have been trying to open up the ways I am looking at my tree. To try and see my tree as a child would, or perhaps even interact with it the way a child would. Results are thus far inconclusive.

Reflection Week 10 - Time Passes, Seasons Change, & Trees Happen.

The recent phenological changes to our Great Nearby would be drastic even to the most aloof of undergrads, I сan confirm. For some reason, when I read the prompt for this reflection, I could have sworn it referenced tasting. So over the week of Thanksgiving break, owing to my on-campus status, I spent a lot of time tasting leaves, usually at different points in the progression of leaf change. It made sense to me that there might be some noteworthy differences. Texture, for starters, which is a big part of the eating process. I encountered many different specimens; some had already fallen to the ground, and others stood sturdy on a branch. Red, yellow, brown, and some green straddlers even. I did make note of the smells--though I would have trouble articulating it, the older leaves certainly smelled more mature. Almost more like nature and less like a leaf, whereas the greener leaves still carried that characteristic smell of leaf, or should I say green? It would seem that grass smells similarly, and a quick google search reveals that the characterization of this odor as “green” is quite common, and it is spawned from carbon-6 alcohols and aldehydes (Hatanaka, 2006). As far as taste, the musky smell of the older leaves carries over. Though neither leaf was fun to chew, the greener ones were certainly more palpable. Stop--what is that you are hearing? Look up--you will probably see many exposed birds’ nests. I have certainly noticed more bird sounds lately. It would make sense since the leaves no longer cover them and thus no longer provide a sort of audio-visual canopy. Oh, how I miss that canopy.

The mood in Hyde Park has certainly been diminished with the going of the leaves; I am particularly saddened to have lost this magnificent canopy right behind Max Palevsky Central, on the little path behind the Reg. It was such a beautiful sight in the Spring. Even more so in the Fall, really a beautiful thing. Now she is all gone--barren and sad. I tried removing flicks of bark from a tree whenever I would come across one, but I never quite found anything hidden within. I had never seen anything different even in more hospitable times, and I chewed that bark frequently as you may recall. Unfortunately, I have not been able to scoop much soil lately. I have been telling myself to do so but without a shovel it can sometimes slip your radar. I hope to gain some new insights after getting a feel for the soil in this “new” environment of ours. I would query that it will be a touch less moist than before.

As far as how these relate to scaling, well, to be frank I am not too sure. None of these processes I have doted on are necessarily unique to our place in town. Or could the scale increase be something that extends beyond Chicago? I suppose if the leaves of every tree across the country fell at once, even the evergreens, that might not be ideal. Leaf dropping are not something that is inherently affected by scale. The soil, however, is definitely something I can see being more localized. Soil quality will no doubt increase proportionally with income; I wonder where abouts the income threshold for a significant change in soil quality would be, using median household income as our measure. Something to think about. I have certainly noticed worse soil conditions in lower-income communities during my wanders.

Reader Photo, Waco Tribune-Herald.

Reader Photo, Waco Tribune-Herald.

Final Reflection:

The initial readings in our class, such as Amateur Eyes, made me realize how much more there was to observation. Over the course of the quarter, I tried to perpetually challenge my observational skills to see through riff raff—to truly observe. However, I found my amateur eyes hard to abandon at times. I was always blinded by my awareness of how much I was missing. I am still learning more about observing as I go about my life in Hyde Park. I feel confident that over time my amateur eyes will mature, especially with the knowledge gained from this fantastic course—Urban Ecology in the Great Nearby. The occasional class excursion helped to reinforce the paradigm shifts in our realm of observation.

Something I have really enjoyed is seeing conversations with friends and family that have come from this course. So often we let trees pass us by that someone closely observing one in your life may cause a rekindling. I have been able to watch many of my close friends commit to “citizen science” projects of their own. Many have begun identifying and logging trees of their own, though that has diminished with the weather. I also recall during my excursion to the Parkway Gardens the conversations I had with residents. I had the opportunity to talk about the grounds and the landscaping

As far as the Shorthand itself, I must admit that I was a little disappointed with how mine turned out. There were a few different factors at play that hindered my shorthand in rather meaningful ways. There was, of course, the incident at Parkway Gardens wherein a young man happened to steal my phone from me. This incident occurred October 30th, and it would be almost a full month before I got my new phone. There was a lot of moments there where I was unable to take photographs when I wanted to—I had to drag a friend with me on walks if I hoped to capture anything significant. Because of the phone incident, it also happened that I was working a lot this quarter. I had two jobs that pretty much kept me busy until 8pm every day. I was up a lot in the night but seldom in the morning, and between classes and work it became harder to see my tree as frequently as I would have liked. I noticed that I have the tree furthest from residency of any of my classmates, and with work and all that certainly became an inhibiting factor. I am still content with the story and tidbits I was able to weave together, all things considered. I really enjoyed the project-based pedagogy that this course employed. Frankly, I wish I could have given this project more of my energy and attention throughout the quarter. I wish I could have taken photos more consistently, and to have continued to hunt my tree down with fervor. Nonetheless I still feel as though there was much to be gained from the project-based approach. I also feel like classes with this pedagogy tend to foster closer or more intimate relationships among classmates, which is always a nice thing. I did enjoy seeing the cast of characters in our class twice a week. I will certainly miss them.

Citations:

Allen R. Kamp, The History Behind Hansberry v. Lee, 20 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 481 (1987).

Cole, David N., and Gregory H Aplet. “The Trouble with Naturalness: Rethinking Park and Wilderness Goals.” Beyond Naturalness: Rethinking Park and Wilderness Stewardship in an Era of Rapid Change, Island Press, Washington, DC, 2010.

Evans, Maxwell. “With Parkway Gardens up for Sale, Officials Hope New Owners Can Revive City's First Black-Owned Housing Cooperative.” Block Club Chicago, Block Club Chicago, 4 May 2021, https://blockclubchicago.org/2021/05/04/with-parkway-gardens-up-for-sale-officials-hope-new-owners-can-revive-citys-first-black-owned-housing-cooperative/.

Haines, Aubrey L. The Yellowstone Story: A History of Our First National Park, Yellowstone Association for Natural Science, History & Education in Cooperation with University Press of Colorado, Niwot, CO, 1997, pp. 240–273.

Hansen, J. M., & Hutchinson , C. L. (n.d.). 57th and Lake Park, pt. 1. Vamonde. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://www.vamonde.com/posts/57th-and-lake-park,-pt-1/10136.

Hansen , J. M., & Hutchinson , C. L. (n.d.). 57th and Lake Park, pt. 2. Vamonde. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://www.vamonde.com/posts/57th-and-lake-park,-pt-2/10137.

Heath, S. (2021, July 27). How to grow samara trees. The Spruce. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.thespruce.com/samara-fruit-3269469#common-pests-and-diseases.

Katz, J. (2005, November 4). More than just slacker image to Ultimate Frisbee. Sports | Maroon. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://www.chicagomaroon.com/article/2005/11/4/more-than-just-slacker-image-to-ultimate-frisbee/.

Kowarik, Ingo. “Cities and Wilderness: A New Perspective.” International Journal of Wilderness, vol. 19, no. 3, Dec. 2013.

Nowak, et al , D. J. (2010). Assessing Urban Forest Effects and Values | Chicago's Urban Forest . Northern Research Station .

Sheridan, Phillip, editor. Washington Park Club Handbook, 1884. Vol. 1, Washington Park Club, 1884.

Smith IA, Dearborn VK, Hutyra LR (2019) Live fast, die young: Accelerated growth, mortality, and turnover in street trees. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0215846. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215846

Straus, Terry. Native Chicago. Albatross, 2002.

University of Vermont, C. for T. & L. (n.d.). OMEKA@CTL: UVM Tree Profiles : Silver Maple : Natural history of the silver maple. Omeka RSS. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from http://libraryexhibits.uvm.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/uvmtrees/silver-maple/silver-maple-nh.