Exploring Urban Nature

A Natural History of my Great Nearby

Meet my Tree

Thornless Honey Locust

Glenditsia tricanthos f. inermis

Thornless Honey Locust

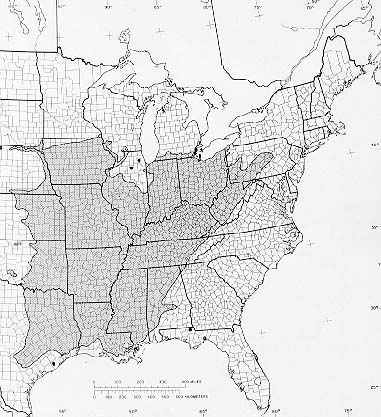

Thornless honey locusts are a cultivar of wild honey locusts, which are native to hardwood forests and river valleys in the eastern, central, and southern United States, including the Chicago region. Honey locusts are drought, frost, and salt tolerant, and grow well in most soil types. Because of this, they're well suited to city conditions, and are commonly planted along city streets and in parks as a shade tree. Honey locusts flower in the late spring from May to June, and seed pods ripen by September or October. They live for about 120 years and can reach a height of 20-30 meters, or about 65 to 98 feet. My tree is about 50 to 60 feet tall with a diameter of about a foot. There are other thornless honey locusts planted along 60th Street and all are around the same height and diameter, so it's likely that they were all planted together.

Honey Locust Native Range (USDA)

Honey Locust Native Range (USDA)

Honey locusts have been introduced in South America, Europe, Africa, Oceania, and West and South Asia. Honey locusts are capable of becoming aggressive colonizers because they produce large amounts of seeds that are dispersed by animals, which has led to them being classified as invasive in New York, California, Australia, and Argentina.

Cultivation and Pests

The first thornless honey locust sold commercially was the Moraine honey locust, originally cultivated in Moraine, Ohio. After father-son duo Clarence and Bob Siebenthaler discovered wild honey locusts without thorns, they found that bud cuttings taken from the wild thornless trees produced thornless propagations, and the first cultivated thornless honeylocust was created. In 1949, the Moraine honey locust was given Plant Patent 836 in 1949, making it the first shade tree to be patented. Thornless honey locust became a popular replacement for American elm trees after Dutch elm disease devastated populations, but the loss of thorns coincided with some loss of pest and disease resistance. Thornless cultivars are susceptible to various pests, including the Lymantria dispar moth, and bacterial stem cankers are common with wounds or dying branches. Some pests, such as the apple wood stainer, honey-locust leafhopper, and treehopper, have been proposed to control honey locust populations in areas where they are invasive.

My tree has Lymantira dispar egg sacs on the trunk and main branches, which may have negatively impacted its health. When I first began observing it, my tree didn't look as healthy as its neighbors. There were a few large dead limbs and the bark was peeling off of the trunk in places, but the leaves seemed healthy and the tree wasn't defoliated, which is a common sign of a Lymantria dispar infestation. It's possible that the dead branches could have been due to poor lighting or natural branch die back, rather than an insect infestation.

Prehistoric Predators

The most striking difference between cultivated and wild honey locusts is the lack of thorns. Honey locust thorns are between three and ten centimeters long, or about one to four inches, and grow on the trunk and branches. On mature trees, thorns may only grow on the trunk, starting a few feet off the ground and ending before the tree canopy. It’s theorized that large thorns evolved to protect developing seed pods from being eaten by mastodons. Fossilized mastodon teeth show that they were adapted to eating tough plant tissues, which could have included honey locust seed pods, so thorns would have been advantageous to protect the maturing seeds. It's thought that thorns only grow in areas that mastodons would have been able to reach, so once a tree was mature enough only trunk spikes were needed to prevent mastodons from pushing trees down for the seed pods. Seed pods were only able to be eaten after they had matured and fallen, allowing viable seeds to be dispersed. Mastodons only went extinct between 13,000 and 9,000 years ago, which is relatively recent in geologic time, so wild honey locusts have retained their thorns.

Uses

Honey locusts can be a valuable food source for livestock and urban wildlife. Cattle, rabbits, and white-tailed deer will eat young trees and seed pods, and grey squirrels, fox squirrels, opossum, and various birds will eat the seed pods. The seeds have a thick outer coat, which allows them pass through an animal's digestive tract unharmed and be dispersed. In the spring, the flowers can be an important food source for pollinators. However, many thornless varieties don’t produce flowers or fruit, and if they do, they produce very few compared to their wild counterparts. My tree, for example, doesn’t have any seed pods on it, but some of the others nearby do.

Honey locusts have also had a variety of human uses throughout history, mainly by Native Americans. The thorns were used medicinally as a painkiller, and the Cherokee Nation used the pods to treat indigestion and measles. The bark was used by the Delaware Nation as a cough remedy, and by the Sac and Fox Nation to treat colds and fever, measles, and smallpox. Fermenting the seed pod pulp can produce potable alcohol, and roasted seeds can be used as a coffee substitute. Honey locust wood is not widely used, but is occasionally used for pallets, fence posts, construction, and fuel. Today, honey locusts are mainly planted as shade trees along city streets and in parks, and as windbreaks in rural areas.

Nitrogen Fixation

The honey locust is a member of the Fabaceae family, which includes beans, peas, and other legumes. Some species in the Fabaceae family are known for being able to fix nitrogen, but there is debate over whether honey locusts have the ability to do so. It was thought that honey locusts weren’t able to fix nitrogen because they have no root nodules, which house the bacteria responsible for converting atmospheric nitrogen to more useful forms. However, studies have shown that both nodulating and non-nodulating species have nitrogen rich tissues. Additionally, both nodulating and non-nodulating species grow well in nitrogen poor soil, and non-nodulating trees like the honey locust will dominate in nutrient poor soil types.

Observations

I first met my tree during week one. I had been looking around at trees as I walked between classes or aimlessly around campus, trying to choose one to observe over the quarter but hadn’t yet chosen one. I took a side path off of the normal route I take to the main quads from my dorm, and I came across my tree. Something about it stood out to me, but I’m not exactly sure what. I liked the location, so I decided it would be my tree for the next ten weeks.

My first observation I remember just looking at my tree and writing down its features, like 3 main branches, a dead branch here, a vine on the side, and so on. I began to use some of my other senses later on. I listened for animals and I could hear birds in the trees, some of which I could identify, like chickadees and crows. I would also hear animals moving around in bushes, and when I looked over I’d see that there were squirrels and birds. In the first couple of weeks I could hear crickets or some other insect in the grass, but as it got colder I couldn’t anymore. The final week, the Midway skating rink had opened up and all I could hear was Christmas music playing over the speakers. As the quarter progressed, I started to smell more. I began to smell dry leaves, which always remind me of the smell of tea leaves, and a piney smell after a storm blew needles and twigs off the bald cypresses. Once more leaves started falling, I could smell damp leaf litter and dry cypress needles, which weren’t as strong as when they were freshly fallen. I tried feeling my tree’s bark, I picked up a rock and dug through the soil a bit. I dissected a honey locust seed pod and found the sugary pulp inside, and the bean shaped seeds. I crushed linden seeds, cypress cones, and beautyberries between my fingers. The one sense that I wasn’t brave enough to use was taste, although beautyberries are supposed to be edible. I still relied a lot on seeing, but I was able to learn different things from my other senses.

From my observations, I’ve gained a better understanding of how wildlife interacts with humans in urban areas. Generally, I was pretty surprised at the amount of animal activity that I was able to observe. I saw robins, sparrows, and what I think were house finches eating berries, and crows and starlings would fly past to roost on South and the Law School. I don’t think there was a week where I didn’t see at least one squirrel. A few times I was even able to see hawks. Overall I was surprised by how comfortable the animals were with human presence. I was able to get pretty close to the birds eating berries, and squirrels weren’t bothered by me at all. Most surprising were the hawks, which were comfortable enough to sit on the lowest branches of the bald cypress.

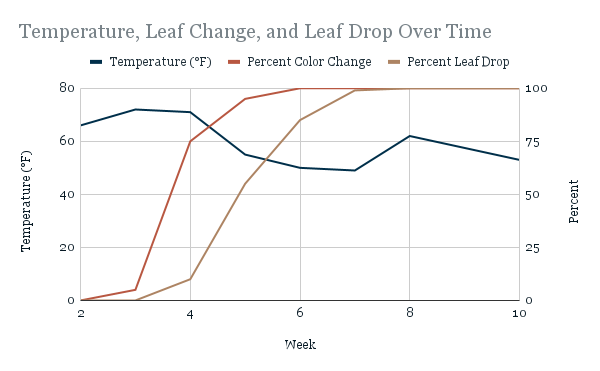

I thought there might be an interesting relationship between temperature, color change, and leaf drop. Looking at a chart with those three sets of observations, temperature trends slightly downward and the percent color change and leaf drop increase, as expected for a tree in the fall. I was surprised by how little the temperature changed, although I definitely skewed the data by doing observations when it was nice out. Maybe it's because this is my first year actually living in Chicago, but I feel like this fall was really warm. I’ve only lived further north so fall comes earlier and I’m used to colder temperatures earlier, but I’ve visited Chicago in November before and I remember it being not nearly as warm.

I have one final question I’d like to answer: does my tree flower? Some of the other thornless honey locusts around my tree had seed pods, but mine didn’t. I wondered early on in the quarter if that was because of a disease or pest but there are no signs for either, other than Lymantria dispar eggs on the trunk. Some thornless honey locusts are naturally infertile and won’t bear fruit, but I couldn't find clear evidence on whether they flowered. If my tree were to flower it would provide an important food source for bees and other pollinators while also providing aesthetic ecosystem services.

Week 1

Week 1

Week 2

Week 2

Week 3

Week 3

Week 5

Week 5

Week 6

Week 6

Week 8

Week 8

Learn the Great Nearby

A Brief History of UChicago and its surroundings

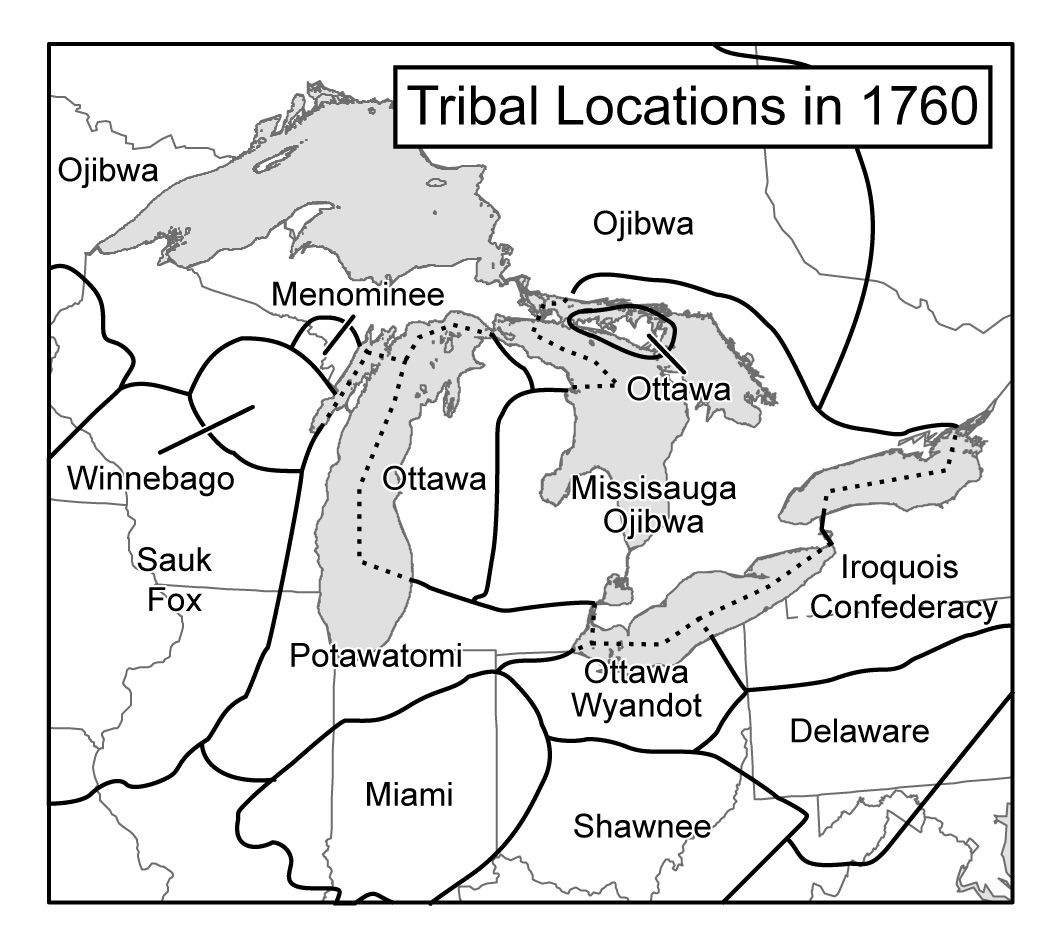

Early Inhabitants of the Great Lakes

Before the Great Lakes region was colonized by Europeans, it was home to the Council of Three Fires, which included the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi Nations, as well as the Miami, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Sauk, Meskwaki (Fox), Kickapoo, and Illinois Nations.

Throughout the 1700’s, Europeans maintained trade relationships with Great Lakes tribes, but the introduction of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 forced Native Americans to move west of the Mississippi River. Those that survived relocation were offered resource-poor land, which contributed to poverty and poor living conditions.

Beginning in 1952, the US Bureau of Indian Affairs began a program offering voluntary relocation into cities, one of which was Chicago. However, relocation did very little to address rural poverty on reservations. People that chose to relocate were housed in slums, and trained on outdated machinery for jobs that were not useful to them back on reservations.

In 1953, the American Indian Center (AIC) of Chicago opened with the goal of providing social services and fostering cultural identity for Native Americans living in Chicago. As of 2018, Chicago was home to 65,000 Native Americans representing 175 different tribes, making it the third largest urban population of Native Americans in the US.

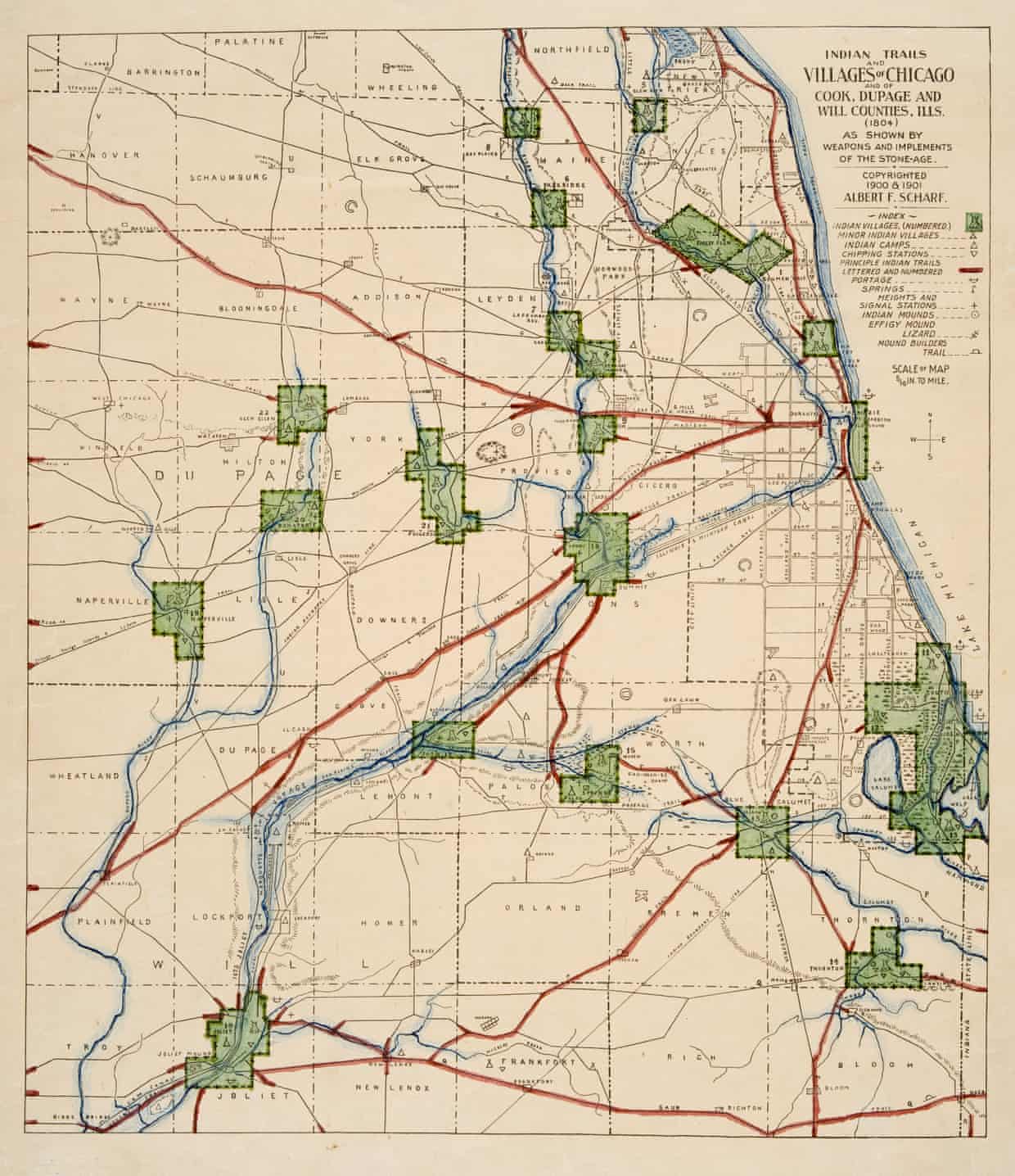

The continued influence of Chicago's first people can be seen in many ways, such as the words Chicago and Michigan, which are derived from Anishinaabe words for wild garlic and large lake, respectively. Additionally, many roads in Chicago follow what were once trade routes connecting Native American settlements.

Native American Settlements and Trade Routes, 1804 (Chicago History Museum)

Native American Settlements and Trade Routes, 1804 (Chicago History Museum)

Tribal territories of the Great Lakes (Skokie Public Library)

Tribal territories of the Great Lakes (Skokie Public Library)

UChicago Campus

Before UChicago and Hyde Park were established, the area was a lakefront marsh, characterized by nutrient-poor soils and sparse vegetation. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, Paul Cornell began to develop the area, and named it Hyde Park. The university moved to its current location in 1891, and in 1892 the first building, Cobb Hall, was built. Efforts were made to landscape, but in the early years a large low spot near Haskell Hall's current location would periodically flood, acting as a reminder for the marshes that once existed where campus now stands.

Flooding on UChicago Campus, 1893 (UChicago Library)

Flooding on UChicago Campus, 1893 (UChicago Library)

Even today there are still issues with water management around campus. I've noticed that every time it rains, huge puddles form on 60th, the Midway, and Woodlawn Ave right in front of paths and crosswalks. I've ended up stepping in them if I'm not paying attention, or having to jump over them to avoid them. The puddles likely form because of compacted soil, blocked storm drains, paved surfaces, and the underlying poorly draining marsh soil. Compacted soil absorbs water more slowly, so runoff is increased, and as water runs off soil and grass, it collects on impervious surfaces such as streets and sidewalks. Normally storm drains would collect runoff, but if a drain becomes blocked by leaves or trash, water will instead pool in the street. Stormwater management can be an issue for urban areas, but Hyde Park is already at a disadvantage by being built on poor draining marsh soil.

Not only does the historic marsh ecosystem affect hydrology, it also affects nutrient availability and plant life. Marsh soil is nutrient poor, and in order for certain trees to be planted fertile prairie soils had to be brought in to replace existing soil. Certain native trees such as the black oak, however, grow well on campus in the native soil.

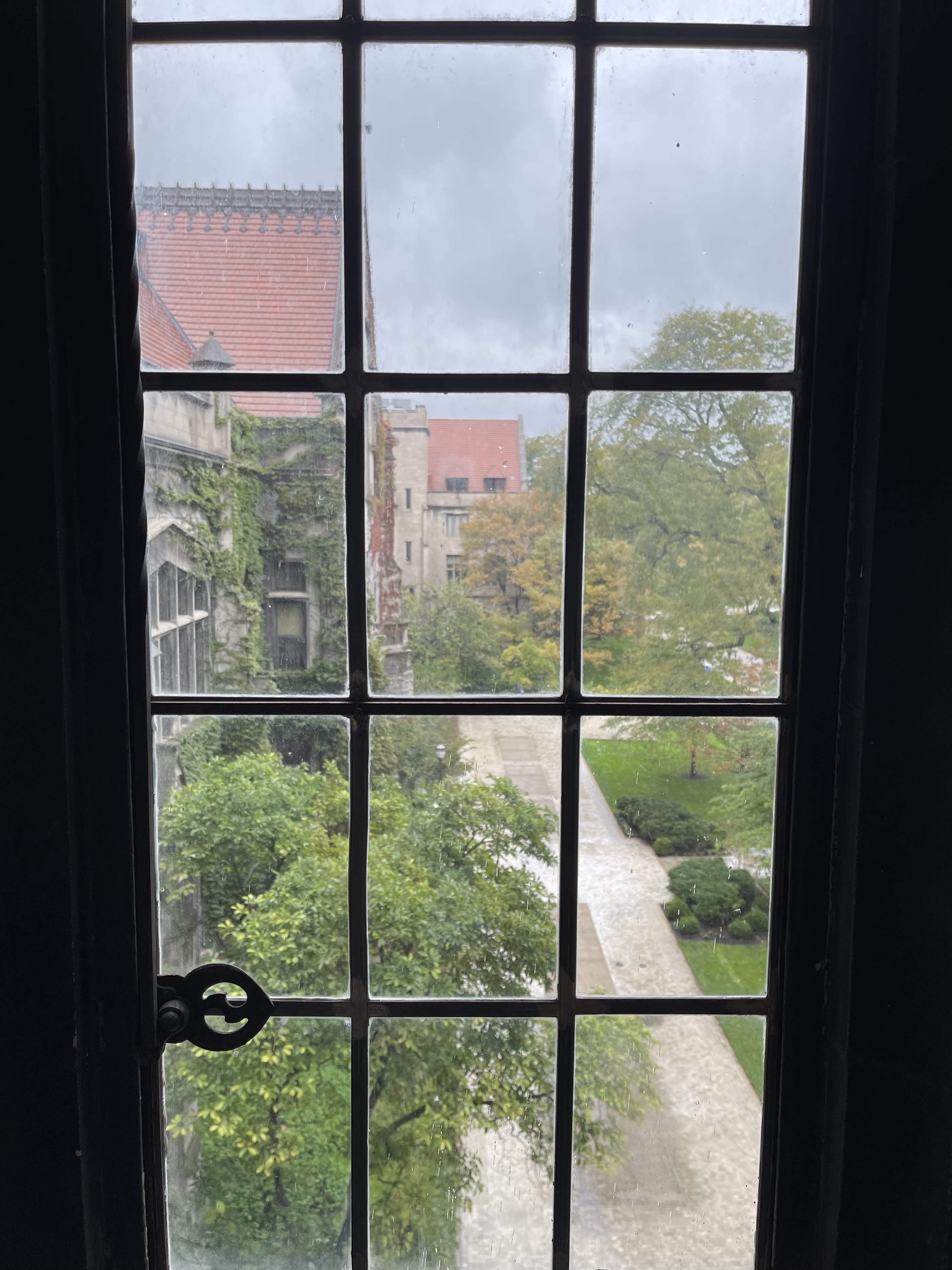

View from Harper West Tower Looking out at Haskell

View from Harper West Tower Looking out at Haskell

The Midway Plaisance

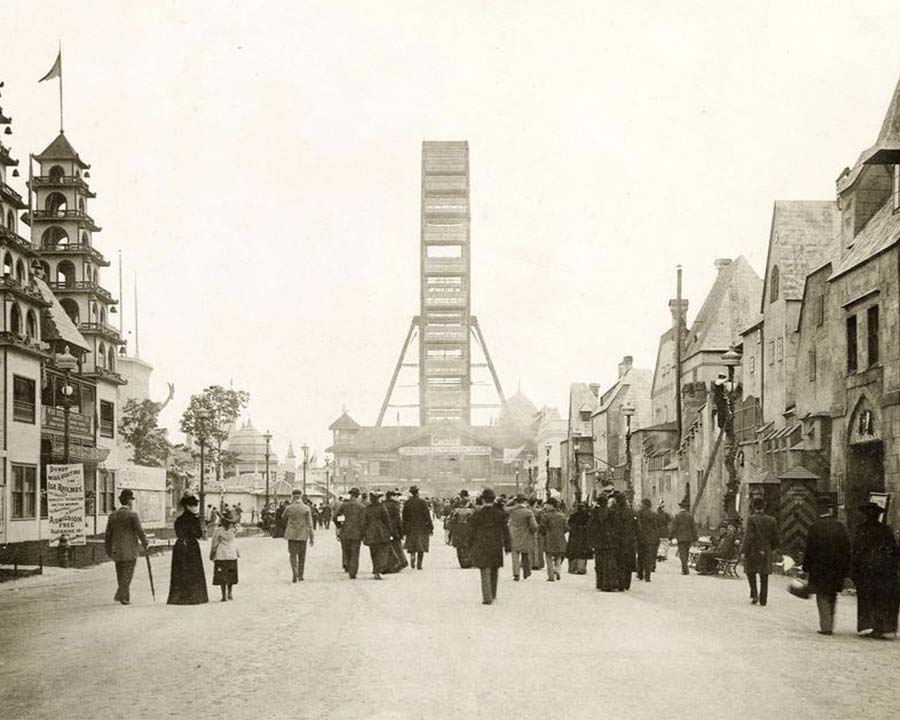

The Midway, Jackson Park, and Washington Park, were originally one single landscape known as South Park. In 1869, the Illinois legislature created the South Park Commission to oversee construction and planning of the space. To design the space the commission chose Olmstead and Vaux, the renowned designers of Central Park in New York City.

Olmstead's plan drew inspiration from Lake Michigan and aimed to turn the marshy land into a series of lagoons in Washington Park and Jackson Park that were connected by a linear canal running the length of the Midway. Unfortunately, the canal was never built due to financial constraints following the Great Fire. Twenty years later, Jackson Park and the Midway were the site of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. The Midway was mainly used for side attractions, such as restaurants, ethnological exhibits, and the world’s first Ferris wheel.

Today, the Midway is bordered by tree lined streets with sunken fields running down the center, and two landscaped gardens, the North and South Winter Gardens, between the main quads and south campus.

There is also skating rink at the original site of the Ferris wheel and 'bridges' that cross the Midway at Ellis, Woodlawn, and Dorchester Avenues, serving as a reminder of Olmstead's original plan and the history of the site.

The Midway is also home to multiple monuments. There is a statue of Carl von Linné south of Harper Library, a monument dedicated to Thomas Masaryk near Blackstone Avenue, and Lorado Taft’s Fountain of Time off of Cottage Grove Avenue.

Statue of Carl von Linné near Harper Memorial

Statue of Carl von Linné near Harper Memorial

Urban Wildlife of the Midway Plaisance

A Field Guide

Taxodium distichum Bald Cypress

Taxodium distichum Bald Cypress

Sciurus carolinensis Eastern Gray Squirrel, foraging in trash can

Sciurus carolinensis Eastern Gray Squirrel, foraging in trash can

Glenditsia tricanthos f. inermis Thornless Honey Locust

Glenditsia tricanthos f. inermis Thornless Honey Locust

Cotoneaster apiculatus Cranberry Cotoneaster

Cotoneaster apiculatus Cranberry Cotoneaster

Callicarpa dichotoma Beautyberry

Callicarpa dichotoma Beautyberry

Tilia cordata Little Leaf Linden

Tilia cordata Little Leaf Linden

Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk

Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk

Parthenocissus quiquefolia Virginia Creeper

Parthenocissus quiquefolia Virginia Creeper

Lymantria dispar egg sac

Lymantria dispar egg sac

Didelphis virginiana North American Opossum

Didelphis virginiana North American Opossum

I chose to make a field guide for Visualize the Great Nearby because I felt like it was the best way to represent the wildlife interactions that I'd observed. I chose to focus on wildlife because I thought that my most interesting and surprising observations involved wildlife interactions.

The Great Nearby Ecosystem

My Great Nearby is multiple ecosystems in itself. My focal tree is its own ecosystem, made up of the tree, insects living on and under it, animals eating it, lichens growing on the bark, and vines using the trunk as support. The South Winter Garden and the Midway are also their own ecosystem. Trees compete for light and nutrients, birds and squirrels use the trees for shelter and food, and humans use the Midway for recreation and relaxation. The Midway is directly connected to Jackson Park and Washington Park, which contain their own ecosystems, as well as the larger urban ecosystem of Chicago.

Wildlife Corridors

The Midway serves as a wildlife corridor by connecting Washington Park to Jackson Park and Lake Michigan. This can increase movement between these areas, and can increase biodiversity. Because of this, some less common urban animals may be found in the park. I’ve seen some less common urban animals on the Midway, such as white-tailed deer and hawks.

However, there are roads and train tracks crossing the Midway, which may limit certain species from moving around while not impeding others. Birds can fly between habitat patches, and squirrels can cross roads with tree branch 'bridges.' Larger mammals, like deer and coyotes, may even use railroads to travel between habitats.

Wildlife Encounters

One of the most surprising wildlife interactions that I've observed has been a squirrel going dumpster diving. I had only ever seen squirrels foraging for seeds or nuts before, and I hadn't considered that our food waste could be an important food source for them.

I've also seen hawks multiple times while walking along the Midway. The first time I saw one I was on the way to class and it was standing in a patch of long grass off of the main path. I wondered if maybe it had caught something to eat and that was why it was on the ground, but I was surprised that it didn't seem bothered by humans. The second time was during one of my weekly observations. For the entire time I was observing my tree, a hawk was perched on a bald cypress branch, and I was able to get close enough to take pictures and identify it as a Cooper's hawk. Again, it wasn't bothered by me, but this time I could see its talons and it wasn't holding anything. The most recent time I was walking by the courtyard near my tree and I saw a different, smaller hawk on another bald cypress. This one was more wary of me and flew away once I got close, but I was surprised it was there at all since the Midway skating rink had recently opened and there were a lot of people around and there was music playing.

Scale

It's important to consider scale when doing such hyperlocal observations. I think that my observations about ecosystem services and the four natures approach may be most meaningful when scaled up to a citywide level. Looking at the total impact of ecosystem services in a city is important in determining how urban nature is beneficial to humans and how it can be improved. Combined with an understanding of the four natures approach, it would be possible to compare the services provided by each of the four natures and illustrate their importance.

I think my observations of animal interactions are most meaningful at the local level. I mainly observed animals foraging around my tree, which I don’t think would be meaningful scaled up to a citywide or regional level. By my tree, beautyberry bushes were popular food sources for birds and squirrels, and I saw squirrels foraging in a trash can multiple times. There was also a large honey locust seed pod drop, which provides another important food source. The same exact composition of species around my tree is not likely to be found somewhere else, so the interactions can’t be scaled up. Squirrels may prefer other foods in other places, such as acorns from oaks on the quads, and they may not have access to others, like beautyberries. There are even differences between individual honey locusts in my Great Nearby. My tree doesn’t produce fruit, but its neighbors do, so animals may interact with the fruit-producing trees more than mine.

The Ecology of Place by Ian Billick and Mary Price focuses on 'place,' or the local context for ecological interactions, and the huge amount of biodiversity on Earth and the difficulties that ecologists can have in generalizing interactions. It applies to my Great Nearby because many ecological interactions depend on place, which can't really be generalized. The interactions that I've observed could be entirely different if my tree were in a similar location in a small city, or even in a different location within my Great Nearby.

Human Interactions with my Great Nearby

Human Drivers, Ecosystem Services, Redlining, and Land Use

Humans as Ecosystem Drivers

Most, if not all, of the species in my Great Nearby are driven by human presence or interaction. Humans are responsible for almost all of the plants present in my Great Nearby. My tree and all of its neighbors were planted by humans, whether as a street tree or as part of a landscaped area, and the surrounding lawns and gardens are continuously maintained by humans. I've noticed little honey locust sprouts around the South Winter Garden that weren't planted by humans, but those will probably get pulled at some point. A majority of the animals that I've seen are common in cities, such as squirrels and sparrows. I'm sure there are many other species of animal that interact with my tree and its surrounding that I just haven't seen by chance.

Biodiversity in my Great Nearby is influenced by humans, mainly by how well a species can survive in a city, and nativeness is not necessarily prioritized. My tree, for example, is a cultivar of a native species, but the reason that is was planted likely wasn't because it's native, rather because it's tolerant of city conditions. Similarly, animals that I've seen are ones that are commonly found in cities, and are likely best suited to living with humans.

Ecosystem Services

Ecosystem services can exist at both the individual ecosystem levels, and can provide many benefits to human well-being.

My tree provides supporting ecosystem services through photosynthesis, by providing habitat, and through soil formation by fixing nitrogen and preventing soil erosion. It provides regulatory services through absorbing stormwater and preventing flooding, regulating climate, and cleaning air pollutants, and cultural services by providing an area for recreating and adding to overall aesthetic appeal. My tree can provide provisioning services through lumber and fruit production, but some thornless varieties don't produce fruit.

The Midway and my broader Great Nearby provide many of the same services at a larger scale. Street trees provide shade and help reduce excessive heat, while also providing a habitat and food source for birds, squirrels, and insects. People have opportunities for recreation, such as biking, walking, or running on trails along the length of the Midway, or skating in the winter.

The ecosystem of my Great Nearby benefits human health in multiple ways. Mainly, the Midway, Jackson Park, and Washington Park are all large natural areas that provide opportunities for recreation, along with cleaning air pollutants and sequestering carbon, which are all beneficial to human health. I've also found a few community gardens close to campus, which can provide fresh produce for the surrounding community.

If I were given the opportunity, one thing that I would do to increase the benefits of my Great Nearby to humans would be to install rain gardens. Although the trees in my Great Nearby help reduce flooding, rain gardens would further reduce runoff and pollution of waterways. There's already a small rain garden behind the Rubenstein Forum, but I am not sure if it actually diverts stormwater. It may only collect water from a small parking lot and patio area behind the Forum.

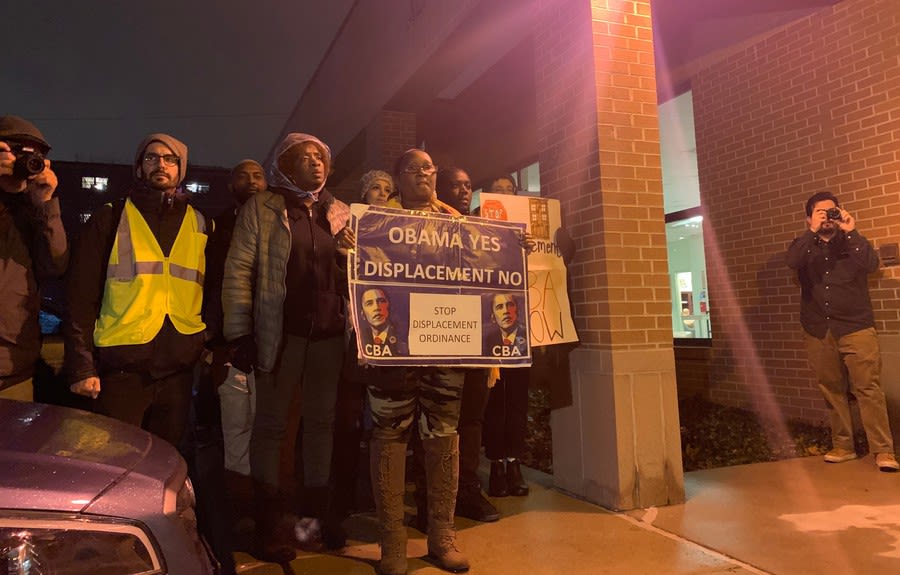

Redlining in Hyde Park and Woodlawn

In my Great Nearby there is a history of redlining and displacement, specifically in the part of campus that is south of the Midway. The university historically used restrictive housing covenants up until the 1930’s and 1940’s to deny African Americans housing within a certain distance of campus. Beginning in the 1960’s, UChicago began expanding its campus south of the Midway, which sparked community protests, which eventually led to a community agreement that the university would not expand south of 61st Street, but Woodlawn residents are distrustful of this promise. Today, community members are pushing for the university to support a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) with the Obama Presidential Center that is being built in Jackson Park over worries that the center will cause an increase in cost of living in the neighborhood, and further displace low income residents.

Redlining has lasting impacts on ecosystem functions and services, and can reduce biodiversity within the area. Redlined neighborhoods have less tree cover, and decreased access to parks and other greenspace, which is reflected in a neighborhood's patterns of land use.

Land Use in my Great Nearby

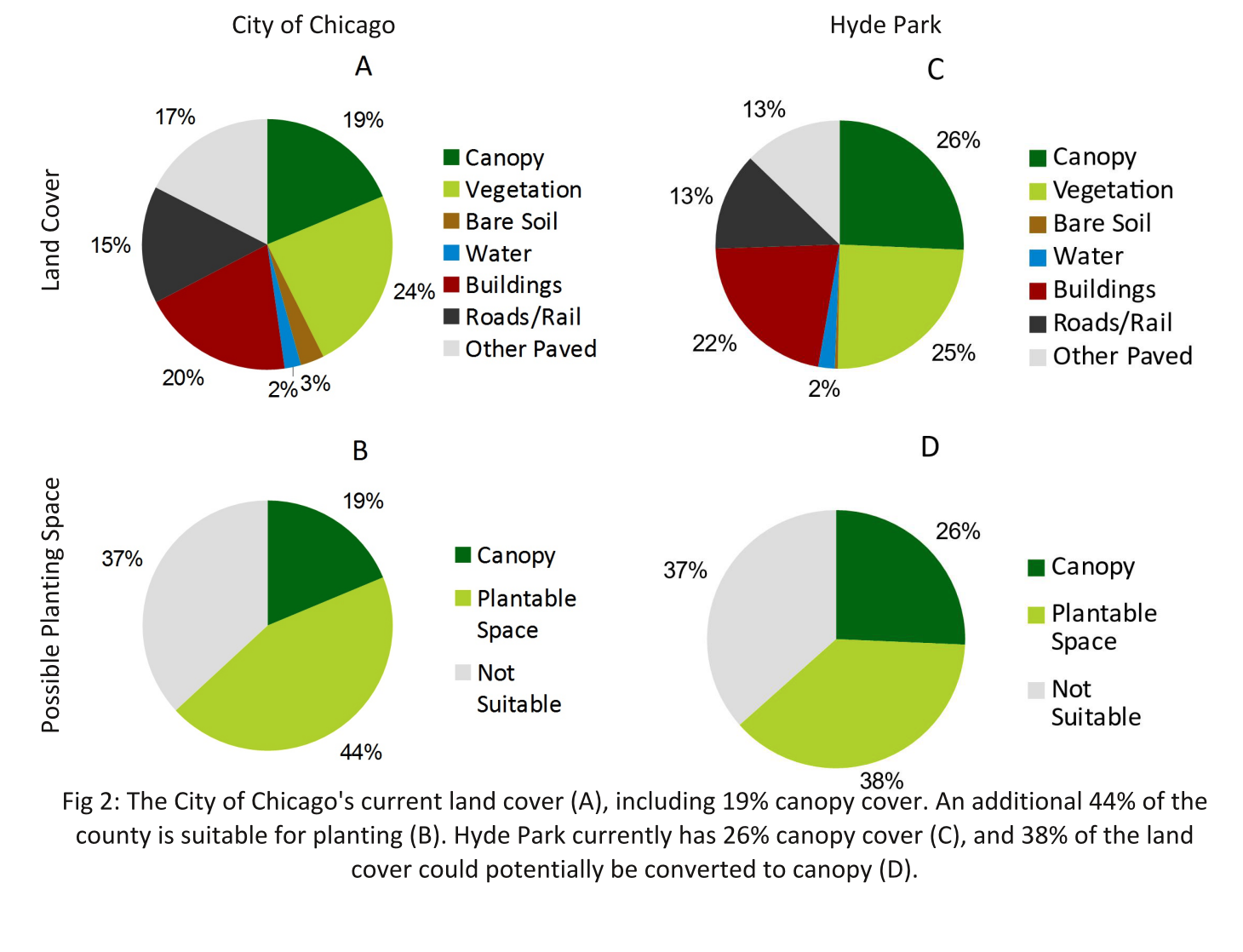

Hyde Park is above average in its urban forest size compared to the city of Chicago, with 26% canopy cover compared to 19% citywide.If all plantable space, or the sum of vegetation, bare soil, and other paved surfaces, in Hyde Park was converted to tree cover, canopy cover could be increased to 63%. 48% of land in Hyde Park is covered by impermeable surfaces, such as buildings and pavement, which is slightly lower than the citywide average of 52%. Residential areas and parks take up a majority of space in Hyde Park, at about 275 acres each. Transit is the third largest type of land cover, at a little less than 250 acres. Compared to surrounding neighborhoods, Hyde Park has the most urban canopy, followed by Kenwood with 25%, Woodlawn with 21%, Washington Park with 18%, and Grand Boulevard with 15%.

A possible spontaneous Virginia Creeper vine on my tree

A possible spontaneous Virginia Creeper vine on my tree

The Brickyard Garden just south of 61st on Woodlawn

The Brickyard Garden just south of 61st on Woodlawn

The 62nd Street community garden on 62nd and Dorchester

The 62nd Street community garden on 62nd and Dorchester

The Woodlawn Organization was responsible for organizing protests in the 1960's (WTTW Chicago)

The Woodlawn Organization was responsible for organizing protests in the 1960's (WTTW Chicago)

Community activists protesting in support of the CBA (The Chicago Maroon)

Community activists protesting in support of the CBA (The Chicago Maroon)

Citywide and Local Land Cover and Plantable Space (CRTI)

Citywide and Local Land Cover and Plantable Space (CRTI)

Kowarik's Four Natures

From observing my Great Nearby, I’ve noticed that my own perception of nature and what is natural has changed. I've found Kowarik’s four natures approach to be especially useful in understanding urban nature, and by reading about the four types of nature and how they are influenced by humans I've become better at recognizing them in my observations.

Kowarik defines four types of nature that are increasingly less pristine due to human influence. First nature is the least influenced, and consists of remnants of pristine ecosystem and mainly includes things like nature preserves. Second nature is more modified, and includes agricultural fields and rural areas. Urban green spaces make up third nature, which includes parks, gardens, and private yards. Fourth nature is the least pristine, and is characterized by novel ecosystems and is usually found in areas with heavy past modifications but little current human influence, such as vacant lots or abandoned buildings and industrial sites.

In week three, we were asked to identify the nearest examples of each type of nature to our Great Nearby, and I was surprised that I couldn't think of any second or fourth nature. Third nature was the easiest since my tree is in a landscaped garden and all of campus is considered a botanical garden. Next was first nature, which I knew could be found in the Cook County Forest Preserves. From there, all I had to do was look at a map and choose the closest, which happened to be the Dan Ryan Woods. Second and fourth nature were harder to find. I originally just looked at a satellite map and found the nearest patch of agricultural fields for an example of second nature, and used the old US Steel South Works site for fourth nature. I was unsure if the area around the Metra tracks was fourth nature since I didn't know if greenery was planted or spontaneous.

First nature is relatively common because of the Cook County Forest Preserves, but most are on the outer edge of the city or in the suburbs, making them less accessible to city residents. Third nature is also fairly common in Chicago, and easily accessible by foot or with transit. I had though that second and fourth nature were not common in Chicago, mainly because I thought of agriculture as large scale farming, and that examples of fourth nature, especially empty lots, are replaced with redevelopment.

Finding Fourth Nature

The concept of fourth nature was entirely new to me when I first read about it. I thought that it was really interesting that entire ecosystems could form on abandoned land once humans had stopped maintaining it, even if our presence was still felt with through things like pollution.

I remember walking around campus one day and coming across a vacant lot on 60th and Cottage Grove and being almost shocked. Not only was it fourth nature that I'd never seen, it was also on campus. It made me realize how little I understood about urban nature since it was so close to my Great Nearby and I'd never noticed it.

A few weeks later, I went out with the intention of finding fourth nature in my Great Nearby, and I was surprised again at how close it was. Just by walking two blocks south of 61st on Woodlawn Ave, I came across two vacant lots, as well as a community garden, which I thought could be a form of second nature. I also found a community garden on 62nd and Dorchester while looking around by the Metra tracks and the campus heating plant.

I was most surprised by what I found by looking around near the abandoned building on 60th and Dorchester. The building itself it pretty overgrown and has a few broken stairs out front. It's clearly not being used, but there is a sticker on one door stating that it's UChicago property. Behind the building is a large fenced in area with a privacy screen and inside the fence there are different trees and long grasses growing. The area doesn't look like it's being maintained by humans at all, and some of the trees may be young enough that they grew spontaneously. I was able to find out that the building was once home to the Hyde Park Day School and the Shankman Orthogenic School, which moved locations in 2014. It seems like since then the building has been abandoned, and nature took over.

I've realized that the four natures don't have to be totally separate. Maintained gardens, which would be considered third nature, can have elements of fourth nature, such as tree seedlings that grow spontaneously. First nature, if not managed, could easily become fourth nature if overrun by invasive species. I've also gained a better understanding and appreciation of fourth nature by being able to observe it myself.

I think the average Chicagoan would view first and third natures as important and valuable, and second and fourth as unimportant or unwanted. Second and fourth natures would be viewed this way because they don't necessarily 'preserve' nature or provide immediate value to people living nearby through services like recreation or beauty. But second nature can support wildlife, and the fringes of fields can be remnants of pristine ecosystems. Fourth nature may not be prioritized because it can be inaccessible since it's most commonly found in abandoned industrial sites or near train tracks or the edge of highways, both of which can be dangerous and usually fenced off.

Final Reflections

The plant life in my Great Nearby has become less dynamic, at least from what I am able to see. I know that as it becomes winter and plants are going dormant they are storing sugars and other nutrients in their roots and trunks for spring, but I can’t observe this visually. I’ve noticed that mammals and birds are not really less active yet. I’m seeing the same number of squirrels, and maybe even more since trees are bare. The same goes for birds, I’m able to see more that might have been hidden by leaves.

I was surprised at how different campus looked when I came back from break. Most of the leaves had fallen over the week and I was able to see buildings in a different way. I’m able to see the stone on buildings that were covered in ivy a couple weeks ago, and I can see buildings from different angles that were blocked by trees.

By focusing on one specific area, my Great Nearby, for the entire quarter, I was better able to understand and apply class topics in my daily life. Rather than reading a text and then discussing it for a week and moving on, I found myself thinking back to different texts and topics throughout the quarter when I was doing observations and reflections. This was especially important in making my Natural History since I was able to recall topics from the quarter and incorporate them into my project.

Reflection was an important tool for me in understanding my observations in a larger context and helping to answer questions. When I would do my observations, I would mainly focus on my surroundings and write down things that I saw, what I heard, and sometimes questions that I had. The reflections helped me revisit my observations after the fact and helped answer some questions or reveal weaknesses in my observations. When I first started my observations, I was only really focused on what I was seeing. I focused only on my tree, hoping to see some animal interaction or come to some important realization. By doing the reflections and seeing some of the weaknesses in my observations, I figured out that I was noticing more when I wasn’t focused totally on one thing. I would hear something, like a sound in a bush, and look over and see a bird. I began to continue to observe outside of the set times just by noticing things while walking around campus, like an interesting plant or a squirrel nest in a tree.

I feel like what I’ve learned in this course will continue to be useful for me. I’m going to be living in an urban area for at least the next few years so I’ll be able to continue to apply urban ecology concepts and gain a better understanding of and appreciation for urban nature as I continue to experience it. I’m also planning on majoring in Environmental and Urban Studies, and I feel like this class was important in bringing the environmental and urban aspects together and introducing a lot of important topics.

I found myself making some revisions to my work when making my natural history, but nothing too major. Some of my revisions were because I had answered a question that I’d written earlier, or learned more about something and changed my mind. Most of my revision came from breaking up assignments into pieces and moving them around my story. Most of the challenge I had with making my natural history was getting it to all fit together and make sense for a reader who didn’t know my Great Nearby. I think my story turned out well, maybe even a little better than I expected. However, I did realize that I had not enough and too many photos. Some things I had overlooked, and other things I had too many pictures of. I had to pick photos that made the most sense in my story and aligned well with the text.

I haven’t yet had a chance to share my natural history, but I’m looking forward to it. I hope it can help other students better appreciate their Great Nearby and the urban nature within it, or help people not familiar with urban nature to realize that it exists in many different forms.